Alex: Good morning, Dan. I’m recording. We are going to talk for an hour or so, and then a portion of that will be put on my blog, as part of my brief (from January 3-20, 2025) ritualistic practice of speaking to collaborators and friends who are doing powerful work with and about audiences, being together, and mutual support in this painful period between election and inauguration.1 (I hope that the remainder of our conversation will be “published” in a legitimate venue, but I’ve been moved by my recently resurrected blog’s capacity to let me move fast, and stay furious!)

Dan: Yes, I see.

Alex: We are going to have a conversation about your amazing and unique performance that ran at the Public Theater in December 2024 in a hybrid situation, that is, both at Joe’s Pub in person (and masked) and online, Dan Fishback is Alive and Unwell and Living in his Apartment. How would you define your experience as the artist, the writer, and the performer, given that you were not there in person, that you were not performing yourself, that you enabled an extension of yourself through another actor. How are you thinking about the audience now?

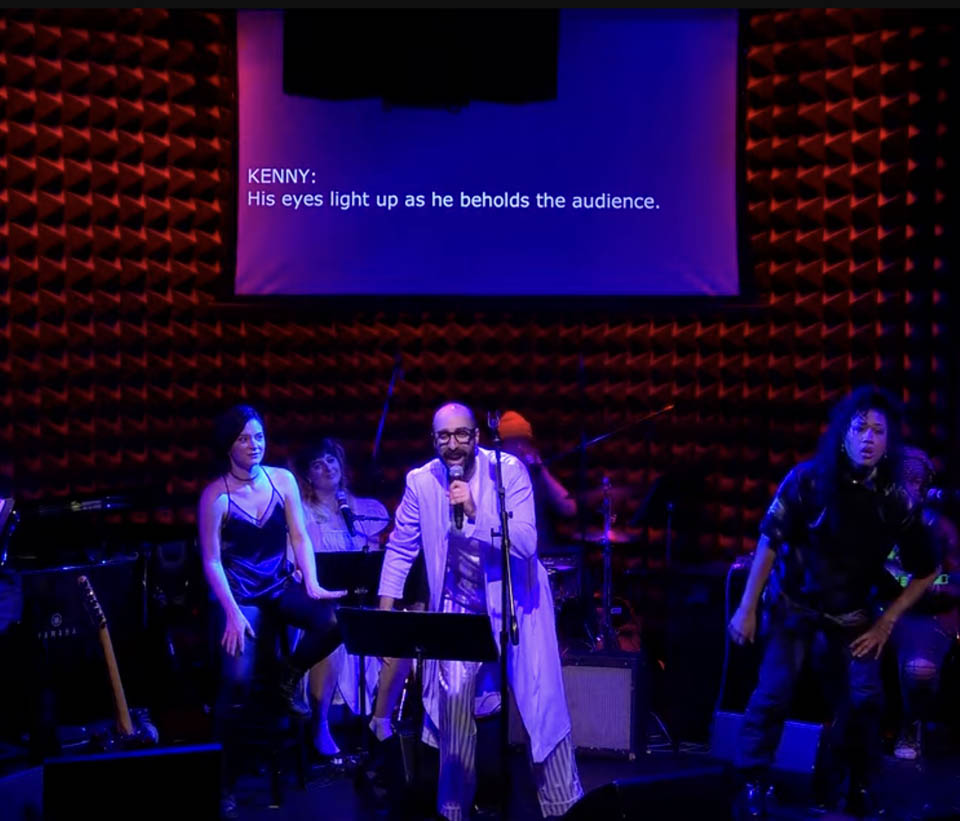

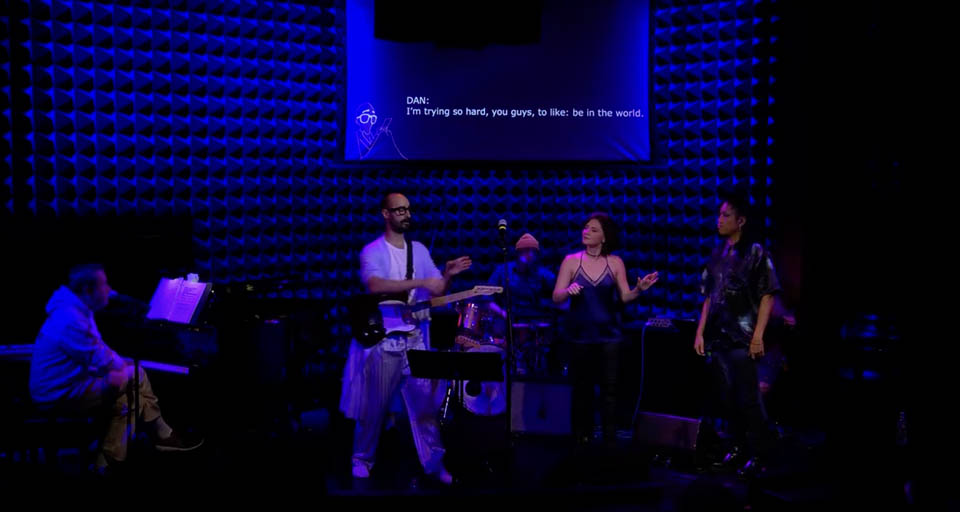

Dan: My understanding of what we were doing shifted tremendously on the weekend that the performance happened. The narrative premise of the show—which is more or less a rock musical; or we’re calling it a play where the only thing that happens is a rock concert—is that I have ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome), so I’m no longer able to perform my own songs. A band of performers gets on stage and they do an esoteric kabbalistic ritual to summon my spirit from my bed in Brooklyn into the body of the lead singer, Ron Shalom, who also arranged the instrumentation of the songs.

And then I, in Ron’s body, have this experience of getting to perform rock music again, which I haven’t been able to do for a very long time. And the show involves integrated access. There are sign language performers on stage, open captions, and audio description.

The audio description of the show sort of doubles as a summoning ritual.

And I knew that there was going to be a live stream of the show. But I did not know until the middle of the first performance that the live stream was going to be live cut from three camera angles. So I knew that there was going to be some kind of feed, maybe giving someone a sense of what’s happening on stage, but not a cinematic sense of what it would feel like to be in the room.

Alex: I love that you’re calling it a cinematic experience. I think that’s absolutely true. You said that it allowed those of us who weren’t there to feel as close as it gets to being there. But I actually don’t want to talk about it that way, and I bet you don’t either. I don’t think that the project of radical or integrated access is about getting as close as you can to the embodied lived experience. It is about producing other kinds of experiences which are equally if differently revelatory.

Dan: Indeed. I have to debunk something. I was physically there. I structured the show so that it would be possible for me to not be there in case I had a health crash serious enough to not be there. But I was at the sound booth in the first performance, and I had my notebook on the table in front of me, and my phone started blowing up in the middle of the show with people who were like, “Oh my God, I’m watching this online!” and these people were effusive. And then I saw what the live stream looked like and I was like, oh, they’re seeing a film, a concert film of our show, and it actually is conveying the flavor and blood and guts of this show.

Alex: That debunking is important to me because a lot of my experience watching it online, thinking about that as a form of radical access, was a kind of imagined co-presence with you, imagining that you were watching it from your room just like I was. I called this “spirit capture,” where I projected for you (and me) a kind of mourning cum joy. I was thinking about you not there: alive and unwell and happy but detached in your apartment. I was having a similar, and also linked, virtual experience very much in touch with a projection of you.

Dan: I wanted the audience to be imagining me at home because, while I knew it wasn’t going to be factually true, it IS true. My assumed absence was expressing something about the alienation that I feel. I was trying to express the feeling of ostracization, the feeling of being outside of social space, being sort of socially dead, a sort of social ghost.

Alex: In a previous post in this short-term blogging practice, joining audiences (and now being in intentional public conversation with others) and thinking about the many ways to be together during the interval between election and inauguration, I wrote about attending an online memorial. We were also supposed to watch Moonstruck at the same time at home on our own computers. A lot of this became an imagining of other people watching the movie “with” me. I started to think about this as a kind of religious projection of a hope that something or someone else is with you. This produces a very beautiful form of audience because it’s full of yearning. And really, your project is very religious, isn’t it?

Dan: The show is insisting that people who have been uninvited from the world still belong in the world, and that even if an accommodation seems ridiculous—like making sure there’s seven people on the stage for the seven lower realms of the sephirot, so that we can do this made-up kabbalistic ritual that I invented in order to summon my spirit into another living person—that even if it has to be as absurd as that, it’s worth it, because every person is worth it. I certainly feel worth it. And what I wanted to stage was a community of people who were willing to be in solidarity with me.

I wanted to intervene into a social landscape where people like me are completely unconsidered, and, rather than telling anyone what to do, just say:

This is what it’s like if you allow me to be present. This is what it’s like if you take the effort to allow me to be present. Something actually spectacular happens. If you listen to me talk about my life, it’s kind of shocking. And you kind of can’t really look away, even when it’s very uncomfortable. And this is all worth it. It’s worth it not to look away. It’s worth it not to let people like me fade into the background. It’s worth it to offer solidarity.

None of the access forms that we used—while all of them were challenging—none of them were extraneous. They all informed our joy as performers and makers. And I think the audience felt that. I get the sense just from talking to people, that there was a feeling of empathetic-ness. And this is what I was hoping for. If the show is being spoken and sung and signed and captioned and described, then there is going to be a sort of emphatic redundancy that will amplify the force of each gesture.

Alex: As an audience member, what those five protocols produce for me was a rapturous sense of presence. Like you are absent and present, and they’re absent and present, and I’m absent and present.

Alex: The show does something else too. You make a connection between political commitments to solidarity focused on people who are chronically ill and also with Palestinians.

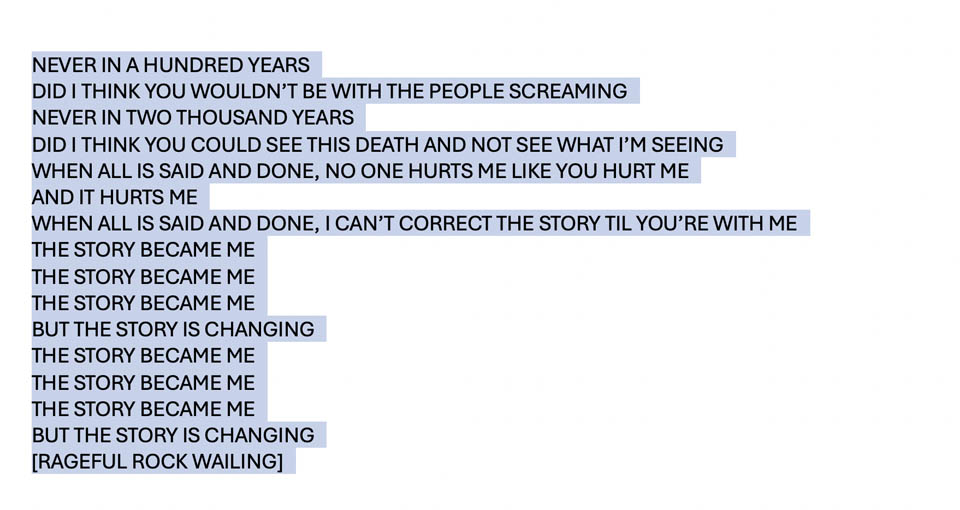

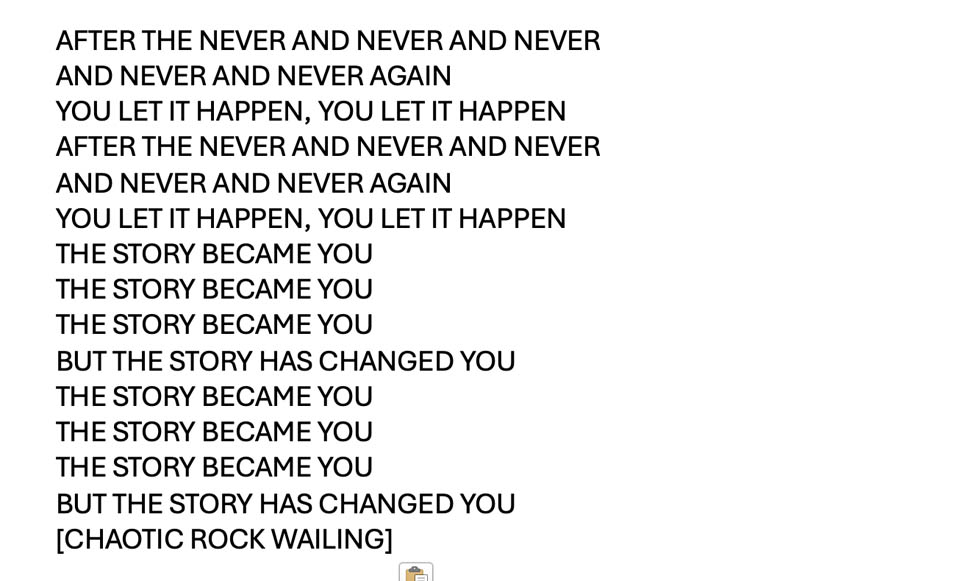

Dan: Originally the show was much less conceptually complicated. I reached out to Joe’s Pub; I said, “I’m not well enough to do my songs anymore. If you have money, I’d love to hire other people to do the songs.” But once the end of COVID mitigation happened, I thought, “I cannot stage my songs about life before, because the end of COVID mitigation for me changed the meaning of everything I’d written. It was a profound rewriting of the rules of civilization. It completely changed my relationship to the human species, seeing people moving on while me and other people in my position were sitting around hysterically reaching out to each other like: what the fuck, what the fuck? We’re just going to be left like this?”

I knew I had to write new songs about that experience. But when the time came for me to build out the score, it was the Fall of 2023, and I was in a daily panic, as many of us were and are, every day calling our representatives and trying to get other people to do the same, and asking ourselves, “What are the ways that I can exert power right now?” because a genocide is happening, and consent is being manufactured, and it’s all happening very quickly, and every day just felt like an emergency.

My body felt like it was on fire, taken over by the images and the video feeds of the genocide happening in front of me. It was just a completely overwhelming experience. And I had to ask myself, “How am I going to make good on my commitment to make this show that is largely about illness while also engaging with this?”

And once again, I relied on the tools Deb Margolin gave me, which are old Split Britches tools. If you’re obsessed with more than one thing at the same time, they’re connected. It’s just a matter of juxtaposing them and finding out what the connection is. And it very quickly felt like the connection is alienation.

COVID and Palestine are two situations where the government and all of our major institutions are saying, “Everything’s fine. No need to get worked up. We got everything under control. Everything’s okay. You don’t have to act. Everything’s fine. Everything’s normal.” And in both situations, I know that nothing’s fine.

Alex: And that’s where you start, Dan. “I’m going to speak as someone who’s chronically ill with an illness many of you haven’t heard of and don’t care about.” “I’m going to speak as a leftist progressive Jew.” Again, a perspective that somehow people, every time you or I say, “I’m that person,” they’re like, “there’s a person like that in the world?“

Dan: This is what I really wanted to convey. You might think that my life is niche or specific, but the concerns that define where I’m at and my position in the world concern every aspect of your life. And you might not think of it that way, but if you look at your life through the frame of mine, you’re going to have some kind of revelation.

- This is my fourth such interview. The first three are with my boyfriend (about the intimate audience, writing, and depression in the interval); the second with Michael Mandiberg (about being audience to another’s need, as that person is careproviding for a partner undergoing chemo); and the third with Aymar Jean Christian (about his work on the African-American cookout as a model for community and mediamaking). ↩︎