Alex: Hi Kyle.

Kyle: Hi Alex.

Alex: Sorry. I kind of hijacked you. I was having a planning meeting with you about our partnership on the imminent release of my new experimental feature documentary, Please Hold (readers, stay tuned!) and then at the very end, I asked, and you so gracefully and graciously agreed, to be interviewed for my dreaded blog, which Visual AIDS (VA) has been on so many times in the last few weeks, as have you personally as well.

I am interviewing people in, this final phase of the practice, who I’m in collaboration with: letting other people speak, not just me, about how you’re thinking about collaboration and being in community. How you’re imagining your audience given that the world is going to change in less than a week. And one of the organizations that I collaborate with the most often since I’ve been back in New York is Visual AIDS.

Kyle: Thank you for your collaboration.

Alex: My pleasure. Can you tell me how your organization is thinking about being in community in this time?

Kyle: There’s a lot to anticipate in terms of policy and politics, but I’ve been trying to understand what if anything is shifting on a discursive level. I am thinking about your timelines of AIDS from We are Having this Conversation Now: The Times of AIDS Cultural Production (with Ted Kerr),1 those broad strokes of how cultural interest and discourse about AIDS change over time, as well as the visibility of queer history, or social justice more broadly.

Until this election, all of those things felt like they were enjoying a general broad uptick: more and more shared language and analysis to talk about sexuality and HIV and race and class and gender. I’m anxious about the backlash against that discourse. A lot of people want to interpret the election as a populist rejection of social justice discourse.

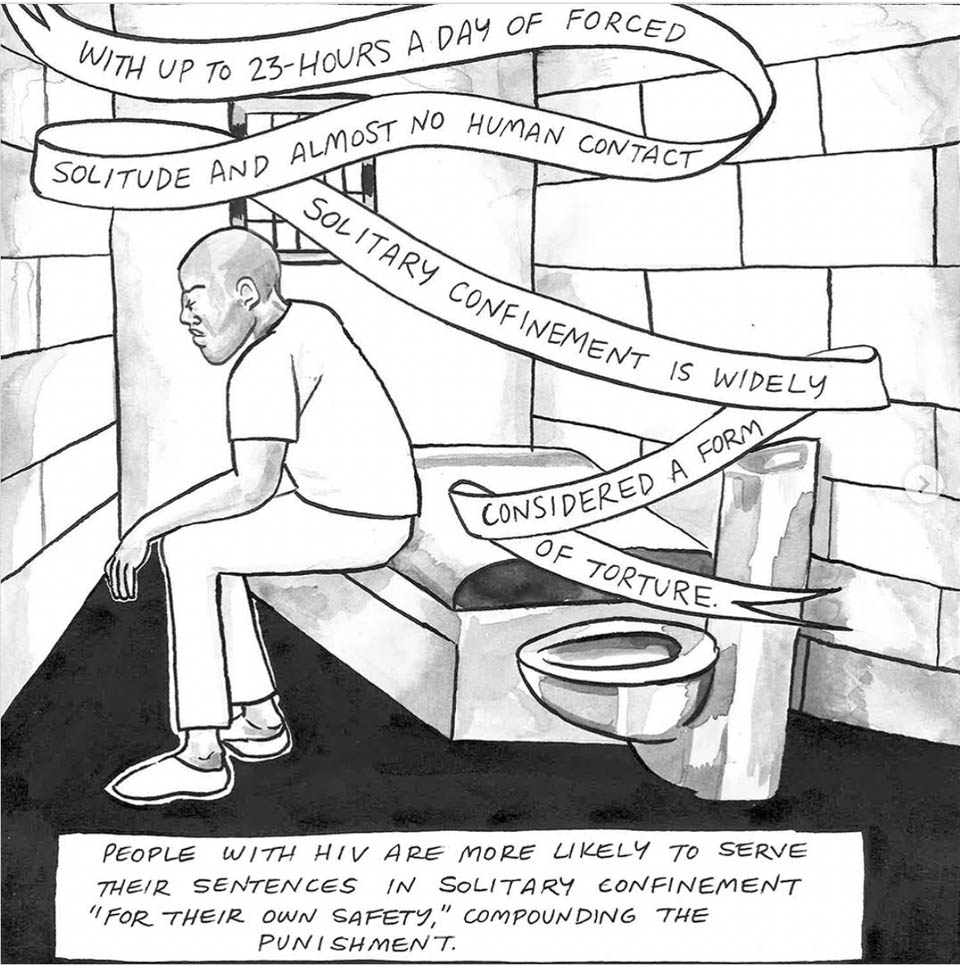

In these moments, Visual AIDS’ job has always been to establish—not a bubble, but a discourse community that says, we care about these things and we take these things seriously. “These things” being the lives and culture of people with HIV, as well as the violence and injustice that is leveled against our communities.

Alex: This is what happens when I have these conversations. My interlocutor brings a framework that I hadn’t thought of. And you brought a framework from something that I had thought of in another context, when I wrote it with Ted—the timeline that he and I produced naming various times of AIDS—which map changes in its discursive life, and hence the lived experience of people with HIV and their communities. Our Times mark how AIDS waxes in and out of language, in and out of volume, in and out of silence, in and out of attention. But Visual AIDS has been there since 1988 and has weathered those surges, sometimes leading and sometimes responding. What is Visual AIDS’s constant project, if there is one, in relationship to the community it serves: artists affected by HIV/AIDS, artists with HIV, and artists who have died with AIDS or related causes.

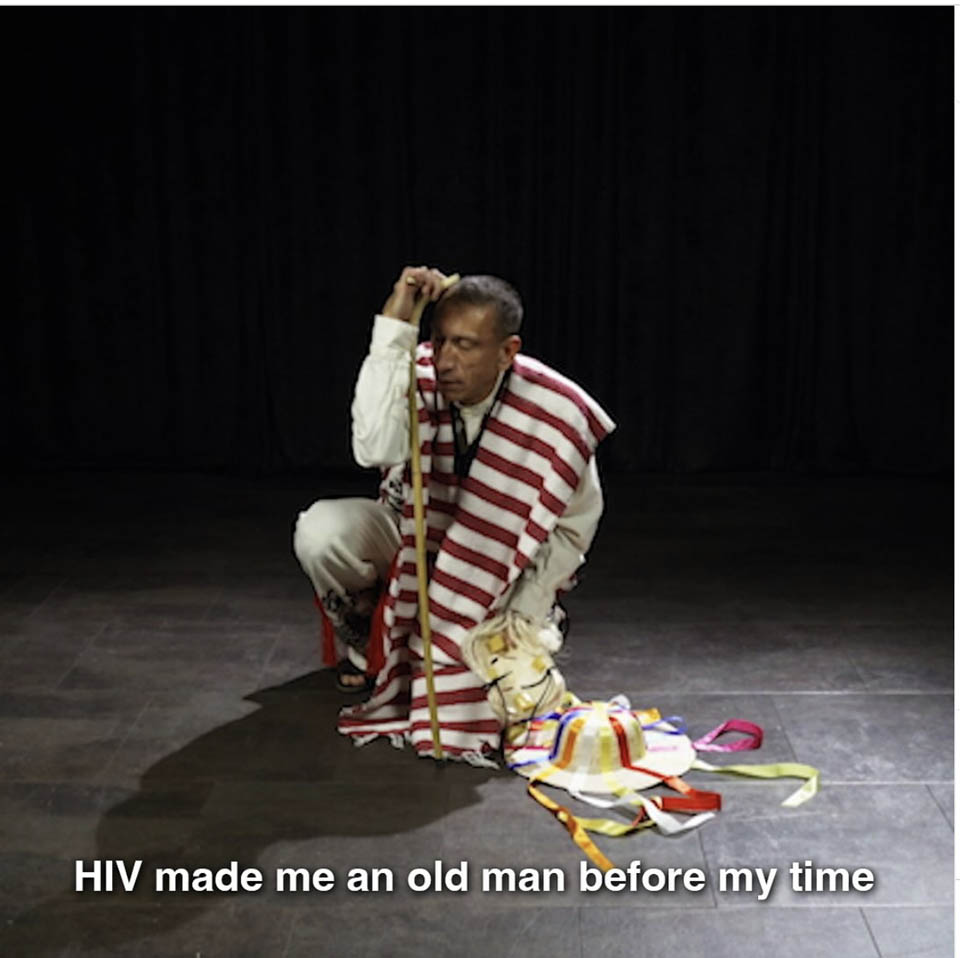

Kyle: Recognition and validation. Providing a historical record for people who were dying too quickly, dying at risk of being forgotten, or who have lived with HIV but feel like they haven’t had access to the institutions that would acknowledge their experiences as historically significant. That kind of recognition is very simple and basic and it is the core of what we do.

Over the past maybe five years, those larger historical/cultural institutions, and broader audiences associated with them, have really embraced our work. People seem to more readily understand the value of what we do. We have been in a growth phase where we can actually kind of surf that wave of interest, which has to do with you and Ted have called “AIDS Crisis Revisitation,” but also COVID and interest in the AIDS movement as a model for contemporary activism. We’ve been able to get MoMA, PS1, the Whitney, the Bronx Museum to engage in bigger and deeper partnerships because our work has been legible and comprehensible in broader national and international discourse in a way that it wasn’t in the early 2000s, for example.

But I’m wondering about the idea that the election marks a sea change. There’s been some criticism recently along the lines of “museums are so social justice pilled, how will that land for a Trump 2.0 public that doesn’t have an appetite to engage with identity politics?”

I don’t totally buy into that, but I wonder if museums will still want to work with Visual AIDS in four years? Are we going to be part of some version of social justice that’s no longer in vogue? A lot of my elevator pitch rests on some basic assumptions—that we value a rich, diverse, and expansive cultural record, that queer and trans lives have inherent value, that art and culture is worth protecting. I don’t think those core values are going anywhere, but I can imagine the next four years might dampen the relative ease with which I can explain to a broad audience what VA does and why it is valuable. (And relatedly, how easily our allies inside of bigger institutions can lobby to their higher powers to secure resources for our partnerships.)

Alex: I think that this idea that Visual AIDS is an identity-based politics organization, that makes a lot of sense to me. All wrapped up in social justice and queer rights.

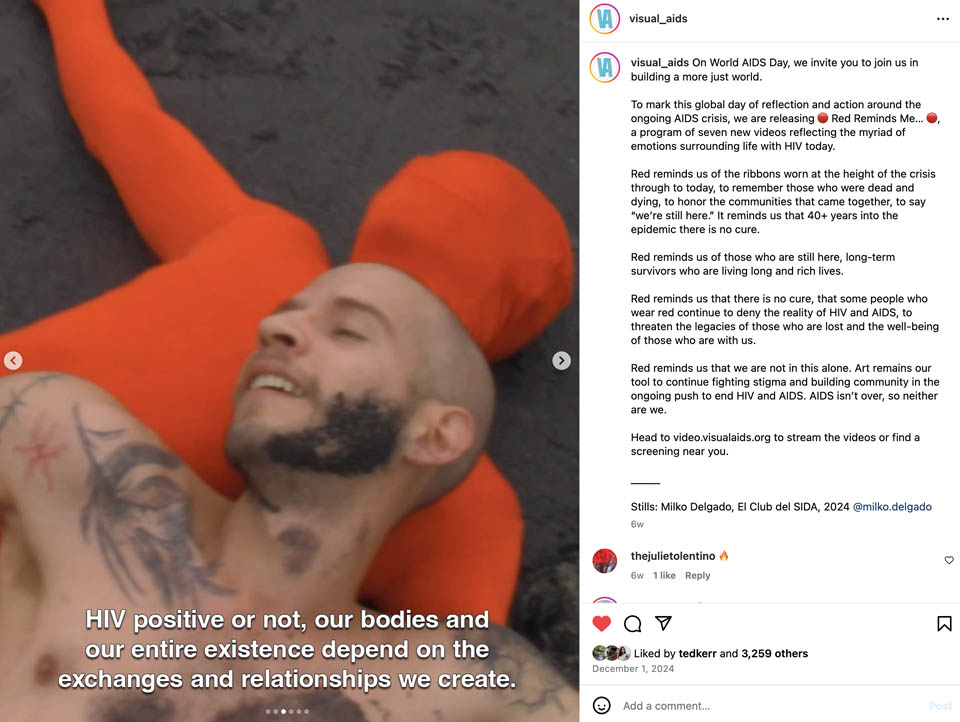

Kyle: I came to Visual AIDS as a young person who had spent a lot of time in the late 2000s hunting for traces of queer culture and political organizing that spoke to something beyond marriage equality. By the time I started interning around 2015, I think a critical mass of like minded people had formed on Tumblr and Instagram and suddenly these legacies didn’t seem so impossible to track down or learn about. I think Visual AIDS happened to be very well suited to that kind of social media/social justice moment and that has grown our audience so much over the last 10 years.

I guess I feel very disoriented because maybe on a personal level, maybe on an organizational level, or a national level, people are speaking very different languages. It’s starting to feel more like the social justice language is a minority, which obviously it’s always been, but there was a kind of majoritarian feel to it …

Alex: … that was amplified by social media.

You know that one of my interests as a scholar and as a human being is how social media functions … and doesn’t. But you use this term social media social justice, and that would be something that I would typically be critical of. But I think you used it in an affirmative way. It’s been good for Visual AIDS.

Kyle: I have been thinking about the way that Visual AIDS embodies institutionality and I think that’s part of what has worked for us on Instagram. We’re saying the kind of radical political things that usually institutions don’t say, but we get to use our institutional voice. And we have the resources that institutions have. We can pay someone to make a cool video for us or pay an artist to make visuals. We get to model or be part of a conversation about what it can look like for an institution to embody a social justice ethics, how you can do institutionality differently. And I think a lot of our audience is excited about that, and they’re excited about accessing the history and the programming that we do knowing that it’s different from other art institutions.

Alex: I think the big question is going to be whether people leave Facebook and Instagram because of the political situation, and how many of social media’s corporate overlords are aligning with our new president and other violent and racist, homophobic, transphobic, Zionist, nativist logics and forces. I think leaving may come to pass. That doesn’t mean that the work you’re doing isn’t going to continue, but it’s going to need to find another home for distribution and connection. And my hope is that that new home is organized around slightly different systems to organize flows of information than has been true for the previous platforms—that have worked so well for you and for so many others, but always and first, are best for capital. We’ll see.

Kyle: I’m thinking about all the slides in our archive and how Nelson and Amy would work so hard to try to get people to look at them in the 2000s. And then Instagram comes along and it’s all just people looking at square images—the perfect outlet for this giant trove of pictures that we have been trying to get people to look at. So what happens after that?

Alex: Hopefully you’ll continue to build out the amazing website that I know you have been responsible for and be part of the solution to invent the next delivery system of squares.

- Kerr and Juhasz, Duke University Press, 2022: https://dukeupress.edu/we-are-having-this-conversation-now. ↩︎

Comments

One response to “social justice. social media”

[…] So while corporatized digital technologies often network and link as ways of potentially amplifying and scaling, what we have seen is linking in order to intensify and come together as opposed to scale and dissipate. – Nishant Shah, intimate links […]