Alex: It is my morning and your evening. Thank you for meeting with me so late, Nishant. Although of course it is very early for me.

Nishant: I think it helps because you are a morning person and I’m a late evening person, so we are both in good spirits.

Alex: I am not entirely in good spirits (given the fires and suffering in LA), but I’m always in good spirits when I see you. So thank you for agreeing to engage in a short interview with me. You are in Hong Kong. I’m in New York. As you know, this is for my short-term blogging practice in which I am currently interviewing people who I collaborate with around some of the questions that have emerged on my blog,1 resuscitated for this purpose during the interval between election and inauguration: about the ways we gather, how we produce audience, how we are in that audience, and models of collaboration that will serve us, at least us in the United States, as we enter a new period in our history under the second administration of our incoming president, who I do not name.

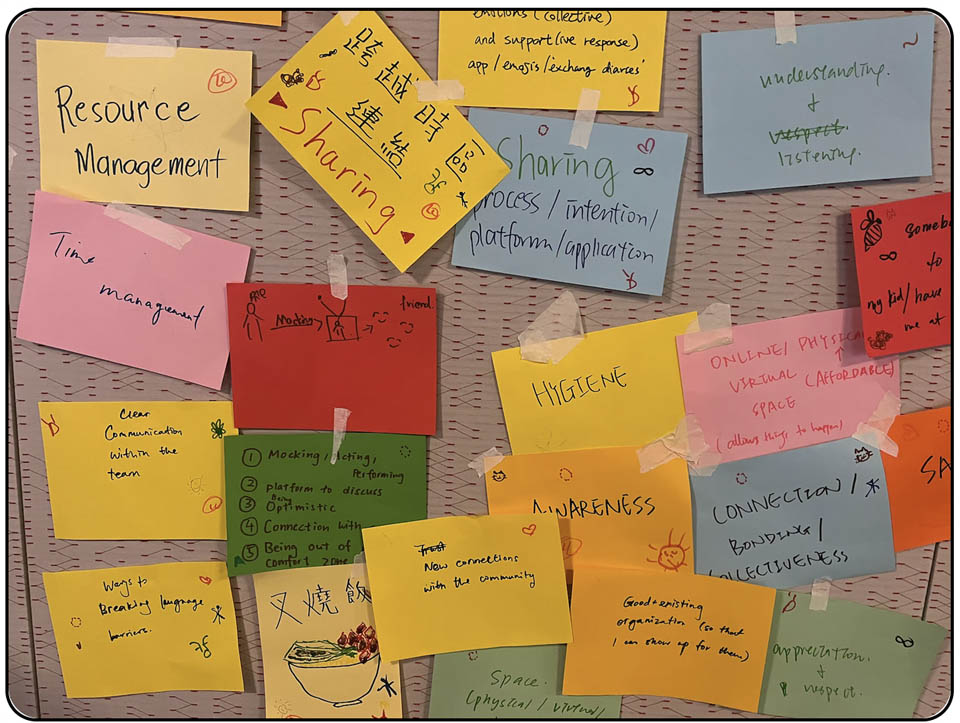

You and I are in a deep and active collaboration right now, perhaps the second (the first was our book Really Fake!) Our new project has us traveling the world, researching and activating on Pandemic Technologies and being together with groups of workshop participants. We’ve been to Hong Kong,2 Delhi,3 and you’re about to come to New York in 2 weeks! Tell me how you’re thinking about ways that we will come together,4 as this world changes so dramatically.

Nishant: One of the biggest learning experiences for me in collaborating with you as we make and run these workshops is that we have developed a very expansive notion of what a technology is.5 We’ve broken the binary to include human technology along with man-made objects. On my upcoming trip to New York for our third workshop, when I know that there are so many natural and political uncertainties that people are experiencing right now, I am thinking about imaginaries of the future as a technological turn, both in terms of futures that we want to arrive at and the futures that we hope will never arrive. I think that is a specific learning outcome from both Hong Kong and from Delhi.

The current political climate, but also the environmental crises that the US has been assaulted by over these few months, make me think of the future imaginary as a technological form. Given my limited understanding of New York—and its narratives of resilience, community, spirit, coming together—when we are working with people there, we are not going to keep on focusing on the present and its immediate aftermaths, but actually think with others about the future as an organizing force. The future, not as something that we have given away or resigned to, but as something that we own and shape. We can center that narrative of us, who we are, what we do, what futures we want to head into. I’m curious about what will happen if we think of a collective future as a technological force that brings us together.

Alex: Just before I hit record on this zoom conversation, we had configured our NY workshop to end differently from the first two with a new activity on Technologies of Hope. Asking the New Yorkers who will attend—and we are imagining a meeting that will only be a few weeks from now, so participants will likely be confused, uncertain, scared and/or already activated, resisting. Can you tell me more about this idea of a technology of hope?

Nishant: The reason why I moved to Hong Kong from the Netherlands two years ago was to set up the Digital Narrative Studio. One of its founding principles is that despair is the privilege of those who can afford it. For those of us who need to continue negotiating with hope—not just for our own safety and security, but especially for those that we deeply care for, and those who we are committed to because we know they need other kinds of activations and resources—we need to engineer technologies of hope outside the interest of these corporatized, platformed digital technologies.

It is in these platforms’ interest that we default to despair because a default-to-despair bias feeds best the neoliberal economic logic of doom scrolling. We doom scroll because there is an infinity of nothingness and there is nothing else to do. So, taking us out of that space and using those very same technologies instead to keep on convening, gathering, organizing, sharing … I’m okay with people feeling angry and hurt and confused and precarious as long as they don’t give into despair. If we center hope and if we keep on using the potentials of these technologies to bring together hope, we can harness those affective states which are incredible resources for forming bonds, kinships, communities, collectives.

Alex: My own short term and personal journey on this blog that now includes my conversations with others,6 continually returns us to human beings producing platforms, systems, technological arrangements under different logics then what has organized digital platforms to date. Both self-evident and yet very hard to do. You and I engender activities in our workshops that highlight some of those human platforms that demonstrate that, actually, it’s not that hard to produce these kinds of affects via technologies (using a capacious understanding of what a technology is).

Nishant: In expanding the notion of what technologies are, we are doing away with objects or platforms or applications or devices, and thus, we have activated a different form of linking. Linking which is relational as opposed to linking which is transactional or extractive. So while corporatized digital technologies often network and link as ways of potentially amplifying and scaling, what we have seen is linking in order to intensify and come together as opposed to scale and dissipate.

It’s not as if the technology comes with the mandate, the intention of scale amplification, which eventually leads to distancing and dissipation. That is the intention of those who write and structure and design it. But what comes up in stories as a powerful form of coming together (explored in a previous project, Doing things with Stories, where we worked with a large community of international change agents) has been precisely that we could use the same technologies to rewrite intentions and mandates and therefore harness intensity and convergence to better suit our needs.

And that forms a different kind of a paradigm. The intentionality of who we link with, what we link to, and what are the kinds of things that activate this action is still something that’s up for grabs and repurposing. It is where for me, the future of the technologies of hope reside.

Alex: Digital technologies and platforms have been so organized by scale connected to capitalist imperatives, but also imperatives of domination. This has led me, from my beginnings as a critical internet scholar, to think about the small and the local and the intimate links between human beings, which I’ve now been calling audience. The link between the two of us collaborating together now over many years, also forms a kind of theoretical structure or maybe a practical structure for how we build out larger gatherings. Our work intensifies by linking to these diverse groups.

So first of all, I just want to say thank you for linking with me! This has been really important personally, but also intellectually, and I think something we share practically as we think together about how do things with the knowledge we gain.

Nishant: Of course, we link within academic circuits as well. We have been linked by the logics of networking, amplification, transactions, and so on. In 2025 (while you were blogging every day), I did an experiment where for one month I did not write about my work on social media. I learned that when I was writing on social media, it wasn’t to get brownie points, it wasn’t to amplify a message, it isn’t to advertise, it is because writing is a form of kinship, and it linked me. And I never thought I would say it in my life, but I missed Facebook because I realized it wasn’t just the transactional nature of it, but because of the intention with which so many people link with me. And in these times, of course I think I’m also going to slowly retreat from Facebook, but there will always be the need for these technologies of linking and the human intentions that shape them.

Alex: You might not know that I’ve pledged, along with many others, to a “lights off Meta©” campaign, January 19-26, which will and will not impact this practice. My last post will be on the 19th or 20th. It can and will live here without those platforms. This dated blog has weathered many platform changes! But without Meta©, I won’t be able to amplify my words here, nor even necessarily fully connect to my “larger audience,” through these habituated paths. That feels very right and also hard: a tough but intentional link to break.

- Here is a summary, “4 questions and 21 audiences at the new year,” of the writing I did from November 20 to January 1, 2025 via the first rubric for my self-imposed practice, one where I blogged, seriously, about every audience I put myself into. ↩︎

- The Technological Pandemic: Continuing to Build a Critical Inquiry Framework, Alexandra Juhasz: https://digitalnarratives.com.cuhk.edu.hk/articles/the-technological-pandemic-continuing-to-build-a-critical-inquiry-framework ↩︎

- Write up of the Delhi workshop by Aditi Somani and Ruchika Dhillon, Khoj Studios: https://khojstudios.org/blog/the-technological-pandemic-the-present-and-future-of-coming-together/ ↩︎

- Coming Together When Nothing is Back to Normal, Dr. Sonia Wong: https://digitalnarratives.com.cuhk.edu.hk/articles/coming-together-when-nothing-is-back-to-normal. ↩︎

- The Technological Pandemic: Building a Critical Inquiry Framework, Nishant Shah: https://digitalnarratives.com.cuhk.edu.hk/articles/the-technological-pandemic-building-a-critical-inquiry-framework. ↩︎

- This is my 11th such interview since 2025 began and there are only a few days left for this inspiring but demanding practice.

1. my boyfriend, about the intimate audience, writing, and depression in the interval.

2. Michael Mandiberg, about being audience to another’s need, as that person is careproviding for a partner undergoing chemo

3. Aymar Jean Christian, about his work on the African-American cookout as a model for community and mediamaking

4. Dan Fishback, about his show, “Dan Fishback is Alive and Unwell and Living in his Apartment,” and what this raises about alienation and solidarity practices with the chronically ill and those in Palestine

5. Chloë Bass, about our collaborating via teaching a feminist class on archives after the inauguration

6. Nick Mirzoeff, about his new book, To See in the Dark, about practicing solidarity between Jews and also with Palestinians

7. Erin Cramer, about her film that I am producing about Valerie Solanas, and taking wisdom from radical feminists and Warholites who resisted in previous moments of American history

8. Bea Hurd and Z. Behl, with whom I’m making a DIY, lesbian, horror film about industrial corn, about the pleasures and power of artmaking in collaboration.

9. Joseph Entin and Mobina Hashmi, about our solidarity work together on the Executive Committee of the Professional Staff CUNY chapter at Brooklyn College.

10. Laura Wexler, about going out together to maintain circuits of feminist connections. ↩︎

Comments

One response to “intimate links”

[…] know that one of my interests as a scholar and as a human being is how social media functions … and doesn’t. But you use this term social media social justice, and that would be […]