Alex: Good morning, Erin. It’s morning for me. And what time for you?

Erin: It is 15:48.

Alex: Yeah, very British of you! I thank you for taking the time to engage with me in a short conversation about a collaboration that we’ve been working on …

Erin: … for a year and a half.

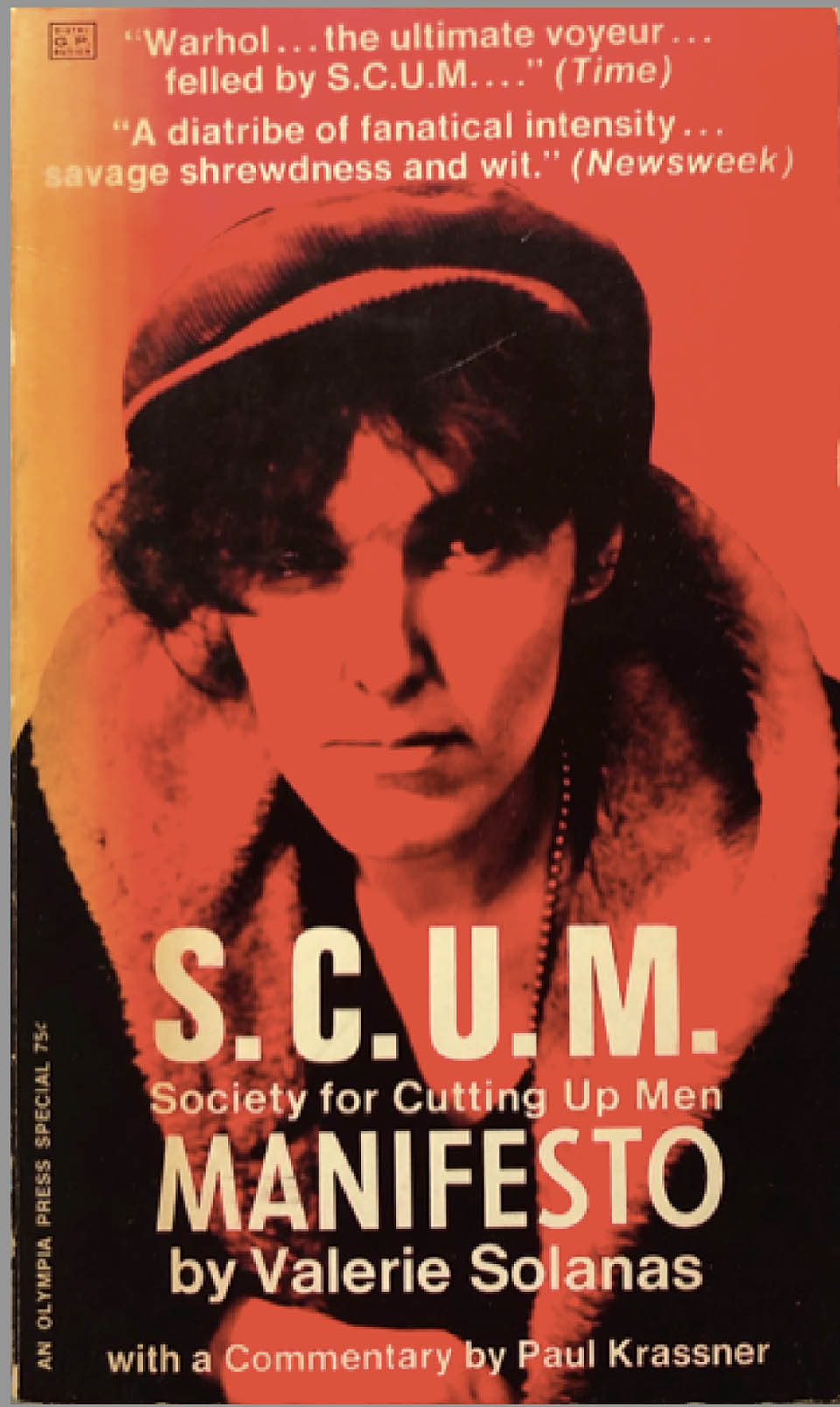

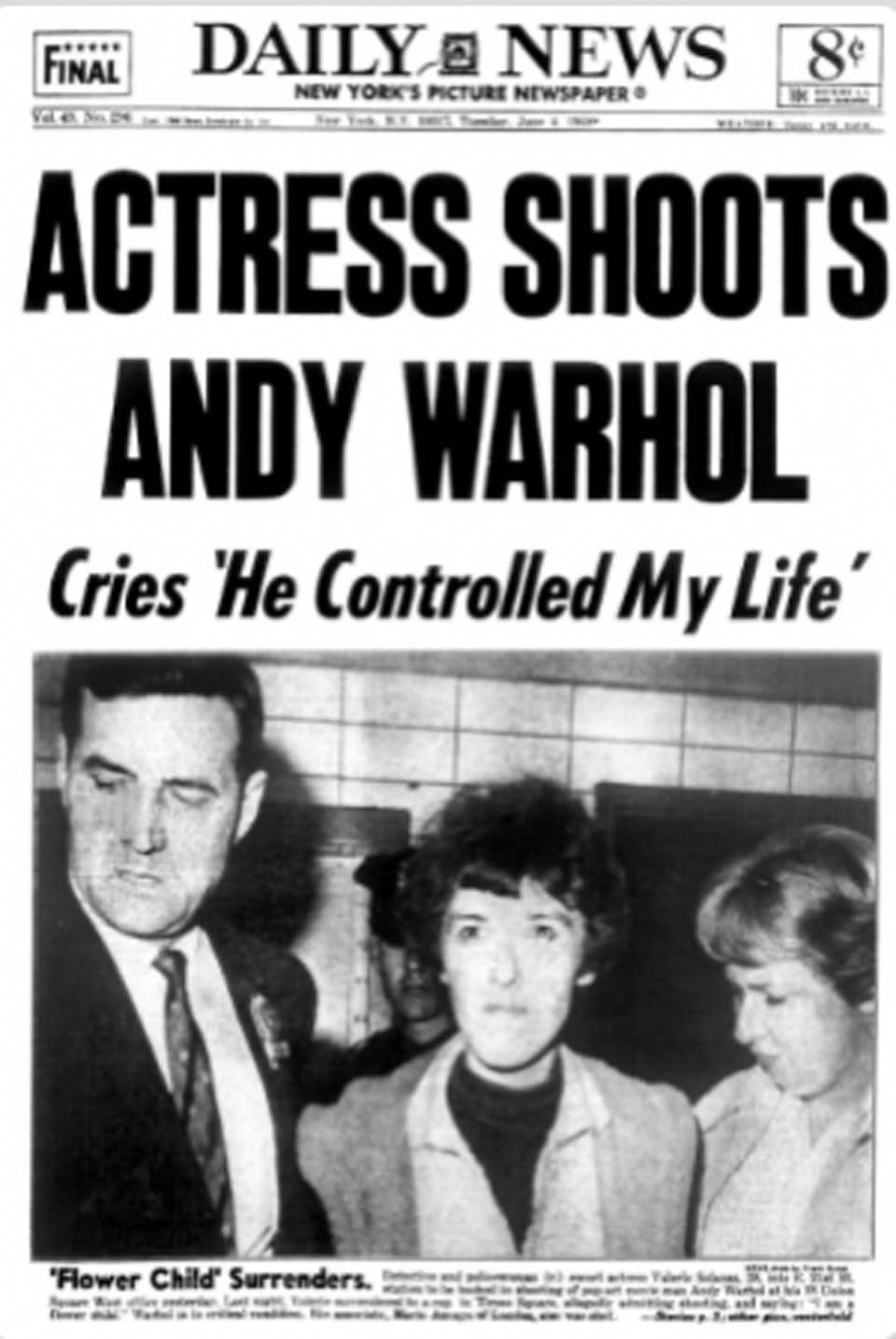

Alex: A docufiction, Civic-Minded Responsible Thrill-Seeking Females, that I am producing, and you are writing and directing about Valerie Solanas, the radical feminist who wrote the SCUM Manifesto and who shot Andy Warhol.

In terms of my blogging practice, which started on November 20, was rebooted by me in 2025, and will last until the inauguration, I’m now in conversation with people about two things, both of which I think you have a great deal to offer about. One is the nature of audience and how that can be a model for encounters that we want in the world we are about to step into. And the other is about collaboration.

On January 20th, we will have a new president in the United States. You live in London. I’m wondering what you think our collaboration will mean for you in that new time, but different country, and what that says to you about collaboration more generally.

Erin: I think we will shift gears because we’ll both feel a greater sense of urgency. It’s more necessary to finish this project and get it out into the world and start to have conversations around it. And while I always felt that the project was going to do those things, and our collaboration always felt meaningful, if we had a Democratic president on the horizon, the first Black female president, I don’t think I would feel the same sense of urgency. So, it gives me a greater sense of purpose. It makes me feel like we have something to contribute to this moment, particularly since Trump explicitly hates women, hates mainstream media, hates left wing media, and obviously hates feminists. It also makes me feel more connected to the issues that the women I interviewed in 1992 were contending with. At that point, women did not have access to legal abortion. Valerie Solanas—who was impregnated by her father and bore his daughter—did not have access to legal abortion. And that’s now true again for so many women in the United States. I never imagined that that would come to pass in my lifetime.

Alex: What’s remarkable about the footage that you shot during the 1990s—powerful interviews with nine people who knew Valerie during the time she was writing the Manifesto that have never been seen; 9 hours of interviews that we’re using for our film—is how these remarkable and astute and political women, say Jill Johnston, Vivian Gornick, TiGrace Atkinson, Flo Kennedy, or Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, they were all talking with you (a young woman at that time) reflect on what had been necessary for them to get to legal abortion and other women’s and civil rights in their times (both in the 1990s when you interviewed them, and during the 60s and 70s about which they are reflecting). They are very clear about what is needed to hold firm the gains their movements had won.

Now, 35 years later, their words are completely attuned to this moment. How eerie that is! But also, how inspiring. Certainly when I taught these tapes (which are not visible to the general public until after we make the film), for a class on this history at Barnard (your alma mater) where we’ve donated them to their archive, the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies students who took it were utterly inspired to hear the ferocity, the political astuteness, the risk, the anger, the power of these radical activist women.

Erin: I have two thoughts. One is these women were all participants in a social movement that created significant lasting change that transformed what our childhoods and our adulthood was like. We are the only generation who had reproductive rights for our entire lifetime.

Alex: And I got to make a family as a lesbian.

Erin: And the women I interviewed made this happen in small groups through the practice of consciousness raising. They were each other’s audience. They were listening to each other. They were showing up for each other. And I know as a documentary filmmaker that the act of filming or even audio recording an interview with someone for films I’ve made, that act of listening and being an audience of one, in terms of eye-line (obviously there’s crew around), this is a very profound act. And so I don’t underestimate what small groups can accomplish and the kind of resonance they can have in the culture and the kind of change that they can evoke.

I think, so far, that’s been our collaboration—for the most of this year-and-a-half it’s been you and me on Zoom, and having various meetings with various wonderful people there, too—but it’s never yet gone beyond an audience of us to each other, or a couple other people. And that’s been incredibly meaningful to me. That could just be because I have so much un-produced work that even having an audience of one sometimes feels like it’s very meaningful, but you don’t want to stop there. I want to make sure it goes beyond just us.

Alex: Crazy! In this short-term repurpose of the blog, twice now, people I’ve been talking with (Nick Mirzoeff on writing his new book, C. Jones on writing poems) discuss the power of writing for an audience of one. In fact, this has happened four times in just about as many days (also, Gavin McCormick on one’s partner as audience and Michael Mandiberg on being witnessed by a friend in times of need). Thinking abut it, I guess it’s not that surprising. I champion the small, and you all know my commitments. Also, this retro blogging and format sort of feels like that to me too: I am writing to a small crowd of compatriots.

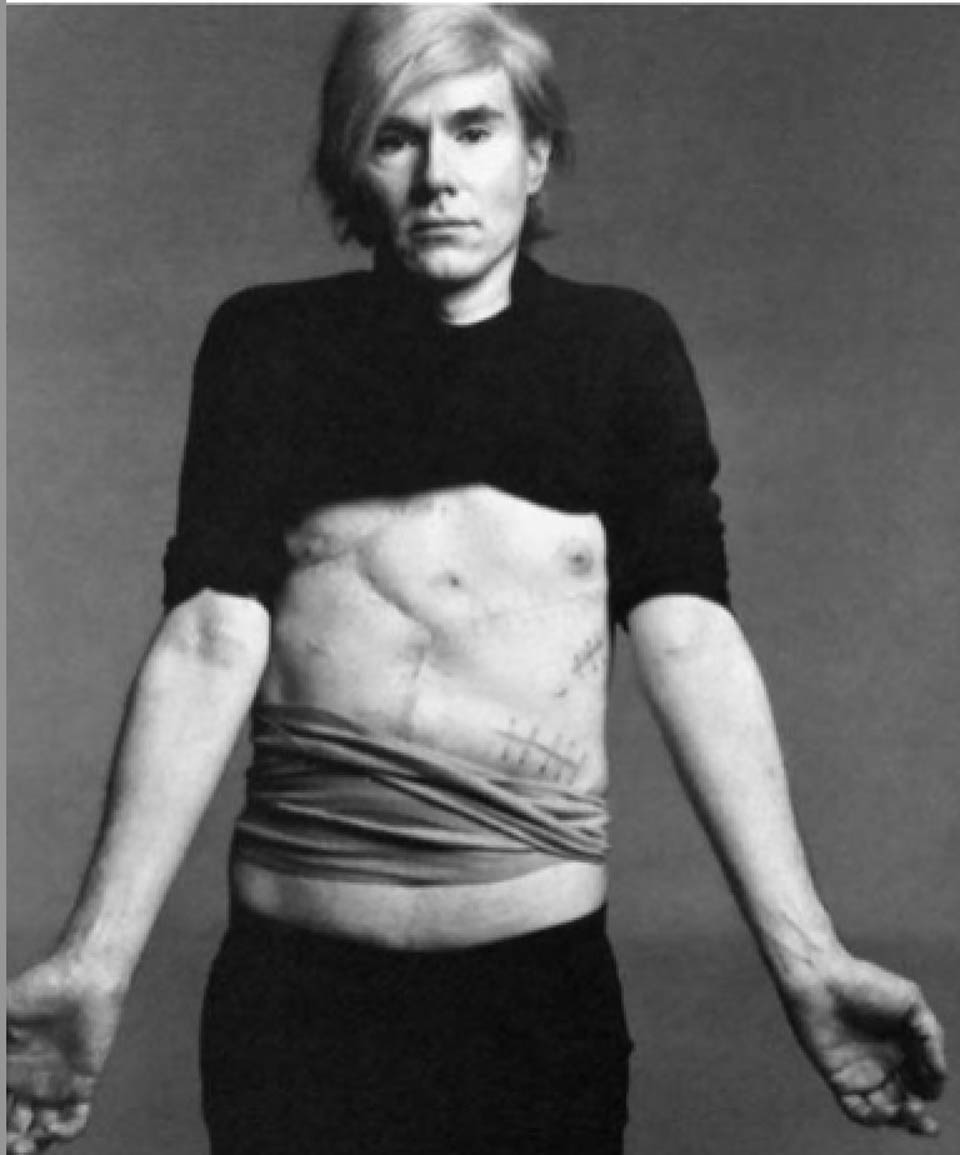

But I am surprised that you noted it because my collaboration with you specifically, and our project—because it was so true for Valerie and Andy as well—revolves around a tension about what one might think of as audience size. Namely, what it means to stay within small and fundamentally radical groups, practices, and relationships to dominant culture, and what it means to grow away from or leave that. Valerie and Warhol were brilliant about these questions, and practices. Both are remembered to this day: Lena Dunham just played her; Andrea Long Chu won a Pulitzer for her brilliant feminist criticism, including that on Valerie’s play, “Up Your Ass.” The way Valerie entwined herself with Andy plays a large part in the ongoing visibility of both of their work. So, very radical Americans can have a larger audience, or influence, or presence. Has your thinking about that changed as we’ve been trying to get into the world a popular rendition of her extremely radical thinking?

Erin: We’ve recently committed to making a smaller version of this project, a 30-minute version of a 113-page feature docufiction script which we both loved. The 30-minute version can come into the world sooner. But I wouldn’t say the project’s self-reflexive, archival, hybrid documentary approach has changed. So, no, I would say that my way of working is to try and make work that is accessible to the broadest number of people I can.

Alex: I have spent my adult working life and social life in rarefied or obscure or radical or edgy communities. I often make the choice. In fact, I suppose I most always make the choice to not follow broadest accessibility in light of those commitments. And of course, I have feelings about that, but that tends to be what I decide. Honestly, it’s not always a decision. I just can’t think, or talk, or produce otherwise. It is a limit, a failing, a strength? And my collaboration with you has been both challenging and beneficial for me because I am trying (with the help of many friends of the film who are better at mainstreaming than me!) to take the expression and experience that comes from a very niche moment and a deeply radical place in American history—Valerie’s voice within radical feminism in the late sixties and early seventies and her manifesto—to a wider audience of feminists. I believe that the SCUM Manifesto is fundamentally available to anyone who wants to learn more about rage, disgust, and anger at the patriarchy. It’s so beautifully written and she’s so smart.

Wrestling about audience was at the heart of the work of both Warhol and Valerie, and many of the people who you interviewed. She wanted half of the world’s possible audience to be exterminated! And so, it’s interesting to watch your interviewees talk about that in the nineties, particularly the two Warholites: Ultra Violet and Jeremiah Newton. And then, there’s also Valerie and Warhol talking about attention in the sixties and seventies, and how her shooting him affected his thinking about as well as his actual fame. Just look where we’ve come in relationship to the ideas that they were wrestling with, about celebrity, art, and radical change, about controlling or entering the flows of capital, patriarchal power and voice.

Erin: People wrestle with why Valerie shot Warhol. But if you take that out, if you just look at The SCUM Manifesto, it is an incredibly accessible text. I think even in its complexity, its extreme proposition of eliminating the male sex, she does it with so much humor that it’s not hard to follow, or love. It’s incredibly entertaining. And Warhol also was no stranger to entertainment.

Alex: That’s why our film will be pop! And I just want to remind you she also expressed a world vision with an end to labor.

Erin: Yeah, abolish the money system and destroy the male sex. Not to mention her original thinking about automation and artificial reproduction. All so that groovy women can do groovy things. As we are now on the precipice of so much more automation than the women I interviewed in 1992 could even have understood, when would be a better time for promoting female leisure and for pursuing groovy things?

Alex: Given these dark times, that’s an inspiring horizon. Thank you, Erin. And thank you, Valerie.

“Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex.”

― Valerie Solanas, SCUM Manifesto

Comments

One response to “groovy women can do groovy things”

[…] The act of filming or even audio recording an interview with someone … this is a very profound act. And so I don’t underestimate what small groups can accomplish and the kind of resonance they can have in the culture and the kind of change that they can evoke. – Erin Cramer, groovy women can do groovy things […]