Alex: Hi Aymar. Thank you for agreeing to have a short conversation with me on Zoom today.

In this second phase of my blogging practice during the interval between election and inauguration, I have decided to be in close conversation with people in my world who can think with me about ways to be together now and later, forming audiences and gatherings that can feed us. I recently had the extraordinary pleasure of getting to see an advanced copy of your comic, The Cookout: A Guide to AI: Ancestral Intelligence, which is part of your larger forthcoming book project, Reparative Media: Cultivating Stories and Platforms to Heal Our Culture. Your work is so deeply aligned with ideas I’ve been invested in for my whole career about community-based anti-racist queer and feminist media praxis, but even more thrilling, things I’m thinking about right now. I am more than happy to host you here!

Aymar: I’m honored. Thank you.

Alex: My pleasure. I have been writing and thinking about and being in audiences in this period, and this has often brought me to the role of food. And here you are having created a luscious body of theoretical and practical media work on the cookout! Can you talk about how food is integral to your project of community building and media making?

Aymar: Absolutely. When I got to Northwestern in 2012, I was new to the city. I had been to Chicago, but I’m not from here. And I spent my first years kind of very lonely. My partner was in LA. After going through kind of a month’s long depression, I realized I needed community. But, how do we actually build it? I luckily knew at least one person in Chicago who happened to be very social, a postdoc at the University of Chicago. And he kind of dragged me out to mostly queer nightlife and some other art events where I started to slowly meet people. And when you go out, you start seeing the same people, you strike up conversations, but in that public space you can only get so deep.

So eventually I realized I need to start bringing people to my home and cook for them so that I can have more meaningful interactions. I was mostly focused on queer artists of color, because those are the people who I feel see me and who share some understanding of what it’s like to be in this world. So sometimes it would be like, oh, come to my apartment before we go out. I’ll have a little bit of food, a little bit of drink, and we’ll kind of pregame and whatnot.

And it was really through that practice that I started to build a community of collaborators, not just people I hang out with and talk to about things. The start of my creative research practice, OTV | Open Television, was with the people who I first hosted. We went on to make films, and they introduced me to other people who wanted to make films and it grew from there.

Food can bridge the public and the private. It can bring people out to the public. But then also when we invite people to our home (I grew up with a family where if you came over, you were offered food and that is how you felt at home), it’s this incredible technology for making connections.

Alex: I have a European parent, a Hungarian parent, and it’s a European or Hungarian sensibility as well, which I don’t see with all Americans. If you’re here at our house, you are going to be fed. But you’re work is about a uniquely Black or African-American or African diasporic food format: the cookout.

Aymar: African-American people have nursed themselves for generations through untold oppression through food, right? When you don’t have complete agency over your body and labor, the one thing you can do actively is nourish yourself to the best of your ability, to sustain your life and the lives of the people that you love. And to do that, they developed something called soul food, which is a blend of African and European and indigenous cooking traditions, ingredients, and so on. And that becomes, I think after slavery especially, a form of gathering community and creating new structures that don’t revolve around colonialism.

I’m talking about this in an African-American context because my parents are Caribbean immigrants. And so this is an ancestral practice. But I do think the term, “the cookout,” is most often used by Black American folks to talk about ritualistic practices of community gathering around food and other forms of art. There’s also music and dance and other forms of cultural expression. It’s a really rich allegorical framework for thinking about how we gather around culture, about food as central to culture, as a culinary art form in addition to other art forms, and how art is this technology for connection.

And so for me personally, my parents love to host. We had this massive backyard, small house, but massive backyard. And so they always wanted to bring their family to their house to celebrate. And of course there was just an enormous amount of food. My dad is on the grill. There’s just these foil platters of all this stuff, some of which is Caribbean, some of which is Black American. There’s the mac and cheese and the potato salad, but there’s also oxtail and curry goat. And it was this mash of cultures and a mash of my family and a way for people to come together even though they were very different from each other.

And I remembered that practice when I was starting to write the book about OTV, all of this community gathering that I had done, and understanding what it meant to be a host, because that’s what I was doing, whether we had food or not. I was holding space and saying, here we are coming together to consume, sometimes food, and in most cases, film and TV stories. And I started thinking how I don’t necessarily love to be around lots of people all the time. So I was like, how did I get it in my head that I could actually do this? And I went back to those cookouts and it became a productive metaphor for thinking about media technology in a community-based way.

Alex: I love learning and thinking with you because I feel like we’re talking about very similar things, but from a slightly altered perspective, which is what difference can do for us! We’re asking a lot of the same questions about making media or art, and thus meaning, in community as a template for living in this world, living in this time, and surviving in this time, one that is quickly transitioning into a deeper and louder and more aggressive form of fascism that was already building. We’re in the interval anticipating that a turn will be happening even more overtly. We might be turning towards something new again, something ominous.

Aymar: I’ve actually been writing a short piece on media and fascism. So this is good rehearsal. I want to go back to 2017, because Venus is going to be in the same part of the sky and in the same part of its cycle in the coming months as it was then. There’s a resonance with this moment. And that time, Venus in 2017, was the most energetic part of the OTV project: we had the most people coming out to screenings, the most energy and enthusiasm, the most ambitious storytelling. It was incredible how in the context of such visible hate, people so clearly wanted to be with those they felt safe around. And we can definitely problematize what “safety” is and how certain people feel more safe than others across contexts.

It was winter in Chicago, there was such energy and actually this palpable love. So obviously, community is so important to survival, just being with each other. Being there for each other in as many ways as we can is everything in the context of an authoritarian, fascist, or however you want to say, regime.

But I think what’s interesting for me about the cookout is how do we cultivate infrastructure around that? How do we make that sustainable? How do we resource the people who take on the tremendous labor of gathering space and holding community, which includes things like accountability?

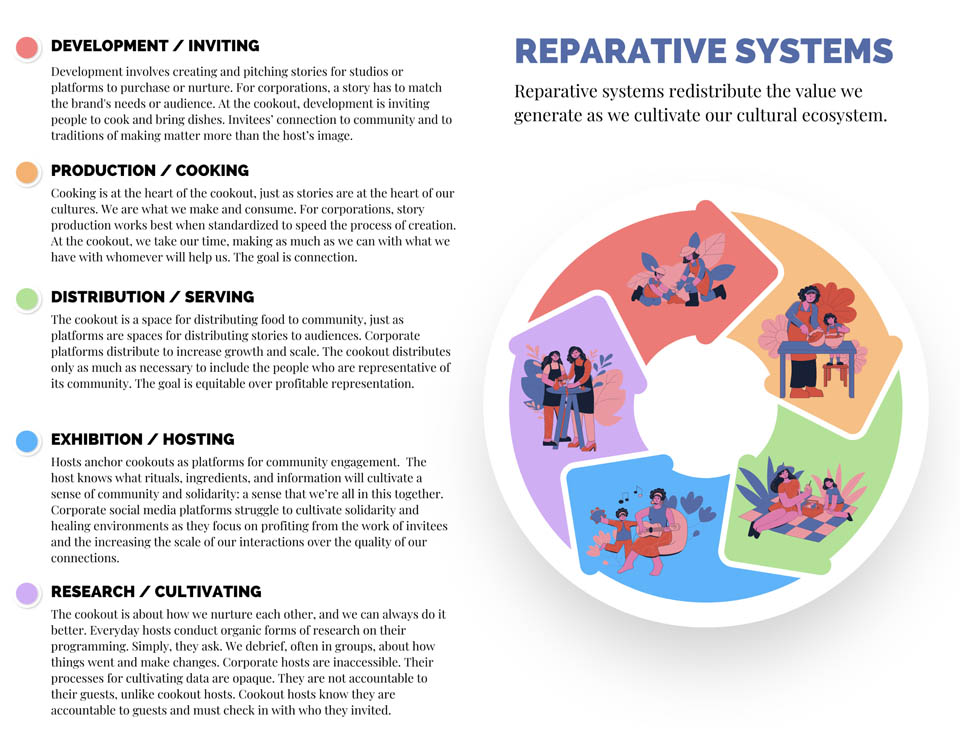

And for me, the cookout is a framework to think seriously about how we develop and distribute community at the same time that corporations and other authoritarian institutions think about developing and distributing capital and power. And so OTV is an interesting metaphor because it’s a kind of Netflix. Netflix can be thought of as a kind of neo-colonial media project. They’re in all these countries, they have two, 300 million subscribers. They want to colonize the world with this very specific form of Hollywood, corporate storytelling. And how do you think about the reverse of that, the underside of that? How do you create your own distribution infrastructure for gathering people around stories and audiences?

And I think your writing is getting at this as well, that audience members need not be passive. They might be sitting on one side of the theater today and then tomorrow on the other side. Together, we can see the complexity of culture, society, and each other in ways that are so important for counteracting the very homogenizing, concretizing, limiting, scarcity-fueled narratives that get amplified in these periods of fascism. It’s such an important antidote, if you can commit to it and sustain and find enough people who want to sustain it. No one person can do it alone.

There’s so many different scales and levels and ways to do cookouts. It’s a framework that gets people to think about: how am I gathering? who is cooking? who’s offering sustenance to the collective nourishment? who is in charge of the space? who’s taking charge? And that can be a decentralized way for rituals, for gathering practices: accountability, the vibe, and new protocols for bridging those who can nourish and those who need to consume. Distribution is technology, and food is part of that, and we can also use digital technologies. Maybe there are new digital technologies can allow us to structure and support some of these community-based infrastructures, whether they be apps or many other things that I’m interested in exploring.

Alex: I love the human labor, the human nourishment, the human interaction that is at the center of how you’re theorizing media making, and the digital, and of course, how you’re practicing. These Reparative Systems of redistribution and accountability, safety and invitation, reciprocity and care, are critical to how we might have power and agency in the groups we make and find and in the times when we’re most threatened. Now more than ever we need hosts, as well as infrastructures to support them.

Comments

2 responses to “the audience as cookout”

[…] one of my interests as a scholar and as a human being is how social media functions … and doesn’t. But you use this term social media social justice, and that would be something that I would […]

[…] Together, we can see the complexity of culture, society, and each other in ways that are so important for counteracting the very homogenizing, concretizing, limiting, scarcity-fueled narratives that get amplified in these periods of fascism. It’s such an important antidote, if you can commit to it and sustain and find enough people who want to sustain it. No one person can do it alone. – Aymar Jean Christian, the audience as cookout […]