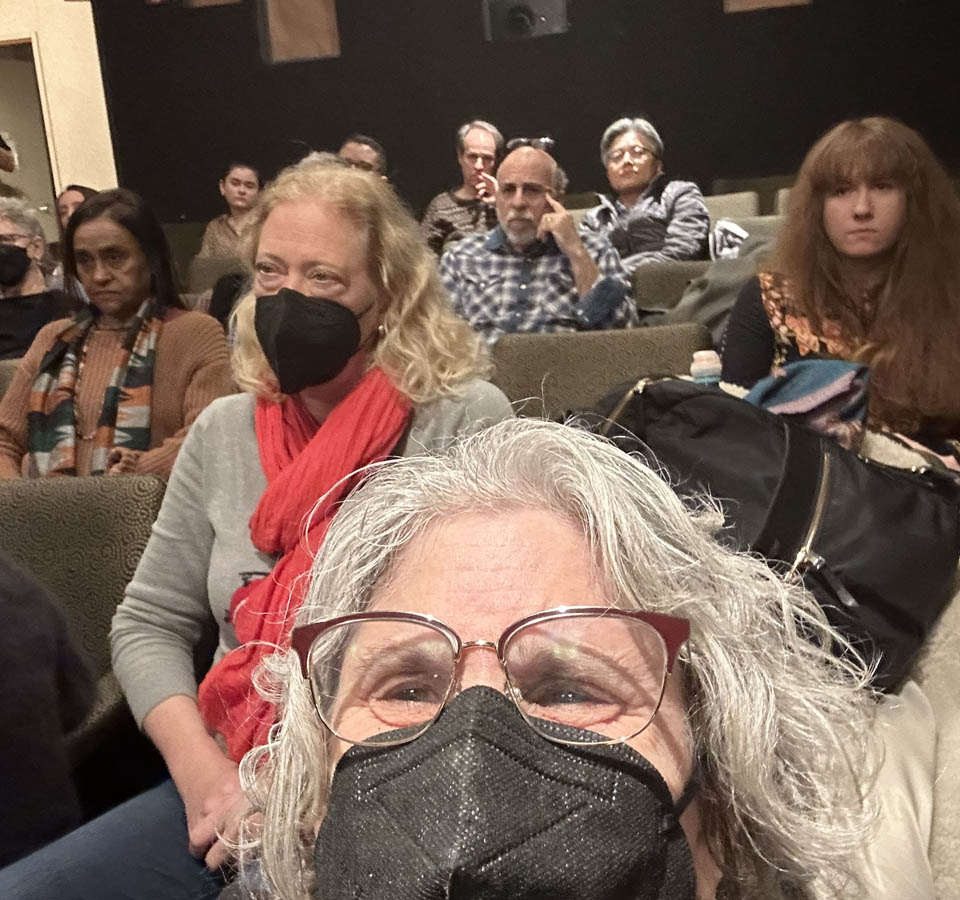

Yesterday, I attended a screening at the Psychedelic Film and Music Festival. On his email invitation, I went to see my Brooklyn College’s Film Department colleague, Mustapha Khan‘s new documentary, Life and Breath. I had no idea what the festival, or really even the film was about. I joined this audience because I was invited and able. Showing up when someone asks is actually one of my core commitments. Founded in an awareness of how feeding it feels when others respond to my own such requests, I have learned that this life-practice can also have the residual effect of nourishing me, by taking me to places, people, ideas, and encounters outside what we now call echo-chambers, thereby making new connections.

Just so, only a week or so earlier, I had gone to see our colleague Annette Danto‘s film, Dindigul Diaries, also on her invitation. In an event called “Reverse Gaze,” her film was paired with In God We Trust, an ethnographic look at one Amish family made by Uma Vangal on a Fulbright from India. Annette’s powerful film also took a long cross-cultural look—over twenty-three and thousands of miles—at the experience of four women who she first met on her Fulbright in Tamil Nadu, India in the early 2000s.

As was true in what I learned about the powerful, persevering subjects honored by Annette, I again received many gifts by learning from Mustapha’s inspiring film. Annette focuses on impoverished but striving workers whose grueling labor is embodied. Meanwhile, Mustapha’s film, event, and audience was situated within the history and doing of a different type of body work: the earthbound, and psychedelic, and therapeutic, holotropic breathwork.

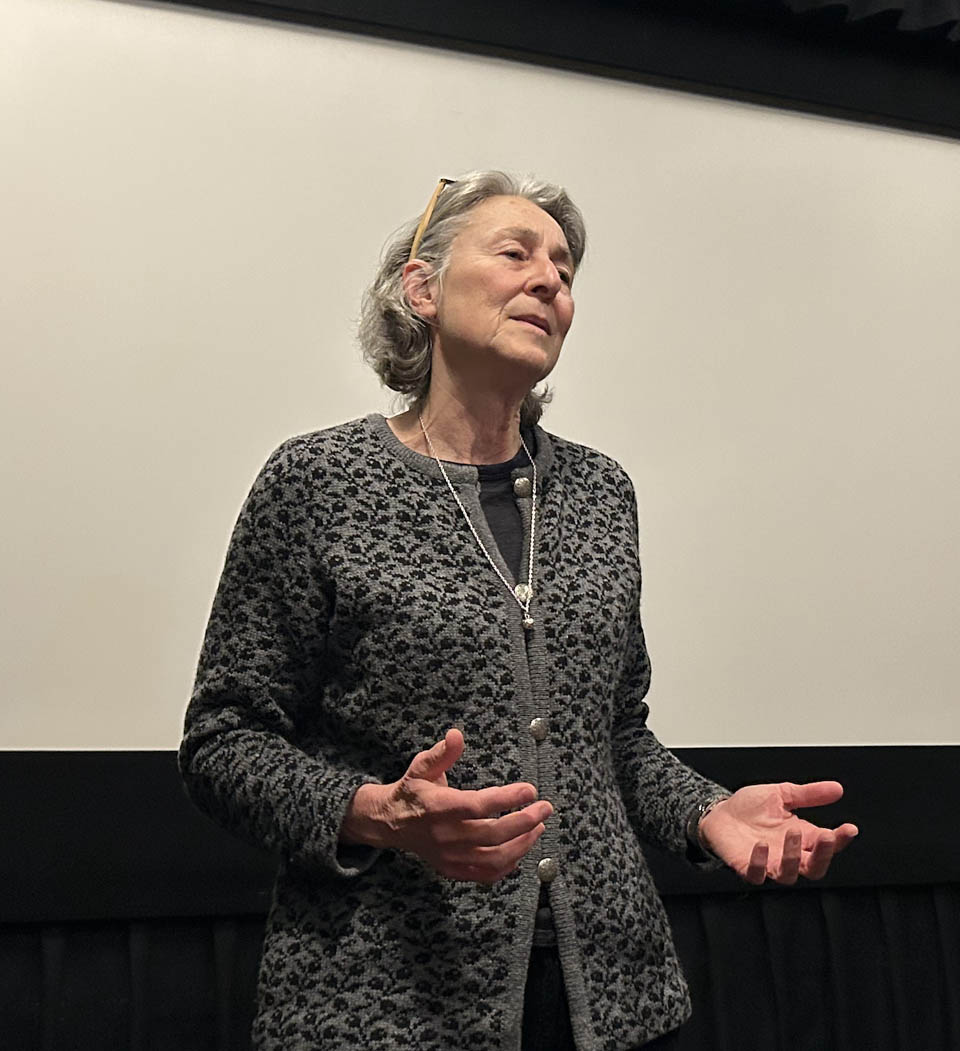

His film focuses on a workshop held at Dreamshadow® in Vermont, led by Leonard and Elizabeth Gibson, and experienced by about twenty participants (some regulars, several new to the practice, even a few skeptics). Life and Breath maps the “basic components” of Dreamshadow® Transpersonal Breathwork: “intensified breathing, evocative music, focused bodywork, expressive drawing, and group process.” As we learn, theirs is a method to anchor the (seeking) self into community by way of clear and simple structures for encounter, learning, and potential growth.

A neophyte to this space (and Dindigul before it), I learned during the film, and after during a conversation between subjects, filmmakers, and audience, that this applied, practice-linked philosophy (like ethnographic film) is a method to take humans to places (within the self) previously un-encountered. Held in a beautiful place, and within a small, in-person, and collective encounter, every Dreamshadow® practitioner is partnered with a caring witness (this perhaps a special kind of audience, one composed of one-on-one watching/doing relations), and then these roles are traded. The breathwork is transpersonal, creating and holding space between diverse humans, and without judgement. I realize this might also be what Danto and Vangal call a reverse gaze: “a new way of making documentaries to ensure that they are presenting cultural identities with empathy and in a non-judgmental and respectful manner.”

Of course, I am a documentary maker like my Brooklyn College colleagues. When I’m in a documentary film audience, I am thinking as much about how as what is made. Given my current practice, I am also attending to how we screen our work, about the many ways to structure and be in audience, and in community, and how to traverse contexts, thereby extending our knowledge from New York screening rooms to southern India, the Pennsylvania Dutch, or metaphysical frameworks.

Yes, I make docs. But in full transparency, I am no “seeker,” even as many people who I love are. I am not religious. I have sought no answers in the mystical, or from drugs, for that matter. I know next to nothing about psychedelics or “new age” practices (other than having been surrounded by them growing up in the 70s in Boulder Colorado). And my own Jewish, non-Zionist, cultural and familial identity and history has become only an awful liability (and ethical investigation) over the past fourteen months (and more).

But, of course, I am on a quest in this particular time- and place-bound practice, one with its own simple structure (on this blog, during the interval between election and inauguration, seeking ways to be fed and feed, within community, to learn and be led, and to be in productive audiences). Leonard and Elizabeth Gibson, dedicated and skilled practitioners and teachers for decades, are most keen to explain how their simplest of methods, requiring very few tools, and no experts, situate the lonely self into a community through defined steps that include talking, listening, art-making, witnessing, experiencing, letting go, committing, and seeking while being grounded and led by clear structures. These are the very practices and methods I’ve been surfacing from the select audiences I’ve been in attendance during this awful interval, albeit connected to different forms, communities, and practices.

Mustapha’s film, and its subjects and their methods, focus on circular patterns of witness and attention. Annette and Uma frame their filmmaking and screenings to include looks back at the filmmaker. Here I link their work to highlight the reciprocity of connection via attendance: a generative exchange; a transpersonal gift.

Comments

3 responses to “In attendance: audience as transpersonal”

[…] becomes an audience through a shared focus on something bigger than the individual, and through a set of processes to guide and keep focused our attention and connection. Why we so often need a piece of art or a […]

[…] focus on something bigger than the individual, or even the intense connection of two, through a set of processes to guide our attention and connection. Why we so often need a piece of art or a sermon, some food […]

[…] I feel more connected to the art that I see, the audiences that I’m in, in a different way, which is not passive. Of course I don’t think I’ve come up with any solutions, and I don’t know that […]