Alex: Good morning, Nick

Nick: Good morning.

Alex: We’re recording and thank you for agreeing to have a short interview with me, which I will put on my blog, quickly.

We are in the last few days before the inauguration. Since the New Year I’ve shifted this blogging practice.1 I have been reaching out to people who I have collaborated with,2 and will collaborate with after the inauguration, to engage in a one-on-one way about the questions that have been central to me in this short period that I have been calling the interval between election and inauguration. I would like to hear you discuss your writing practice in the last 15 months and your sense of its audience.

Nick: Writing became a way of handling what was otherwise unspeakable. And I mean that in two senses. We have for a long time said that politics is the relation of the visible and the sayable. But I think in this case what’s happened is it’s the relation between the visible and the unspeakable. And I mean by unspeakable that it’s appalling, it’s awful, the things that we’ve seen. And it’s also unspeakable in the Western context because you’re not allowed to say it. It’s verboten. It’s taboo. People get fired for using certain words, for posting certain words on social media.

It seemed to me, really, I didn’t have a choice about it. It’s not like I sat down and thought, “maybe I’ll write something.” This isn’t how it happens at all for me. I had no choice but to do this because immediately after October 7th happened, I knew what was going to happen next. Of course, I didn’t quite realize the full extent. You knew something appalling was going to happen. You also knew it was going to happen in your name. Pre-October seventh, I would have said something equivocal like “I’m a person of Jewish descent.” “I’m a Jew and what is being done is supposedly for me.”

My writing was something that I needed physically, chemically to do to try and come to terms with all this change of state. And that very much relates to the second part of your question, which is audience. Because I knew that there were others—some of us Jews, many of us actually—and we met together in person to have these kind of sotto voce conversations where you could start to use the word genocide with others. Now people are saying it, but it was hard at first with all those vans centered in Manhattan blaring out about the hostages and so on.

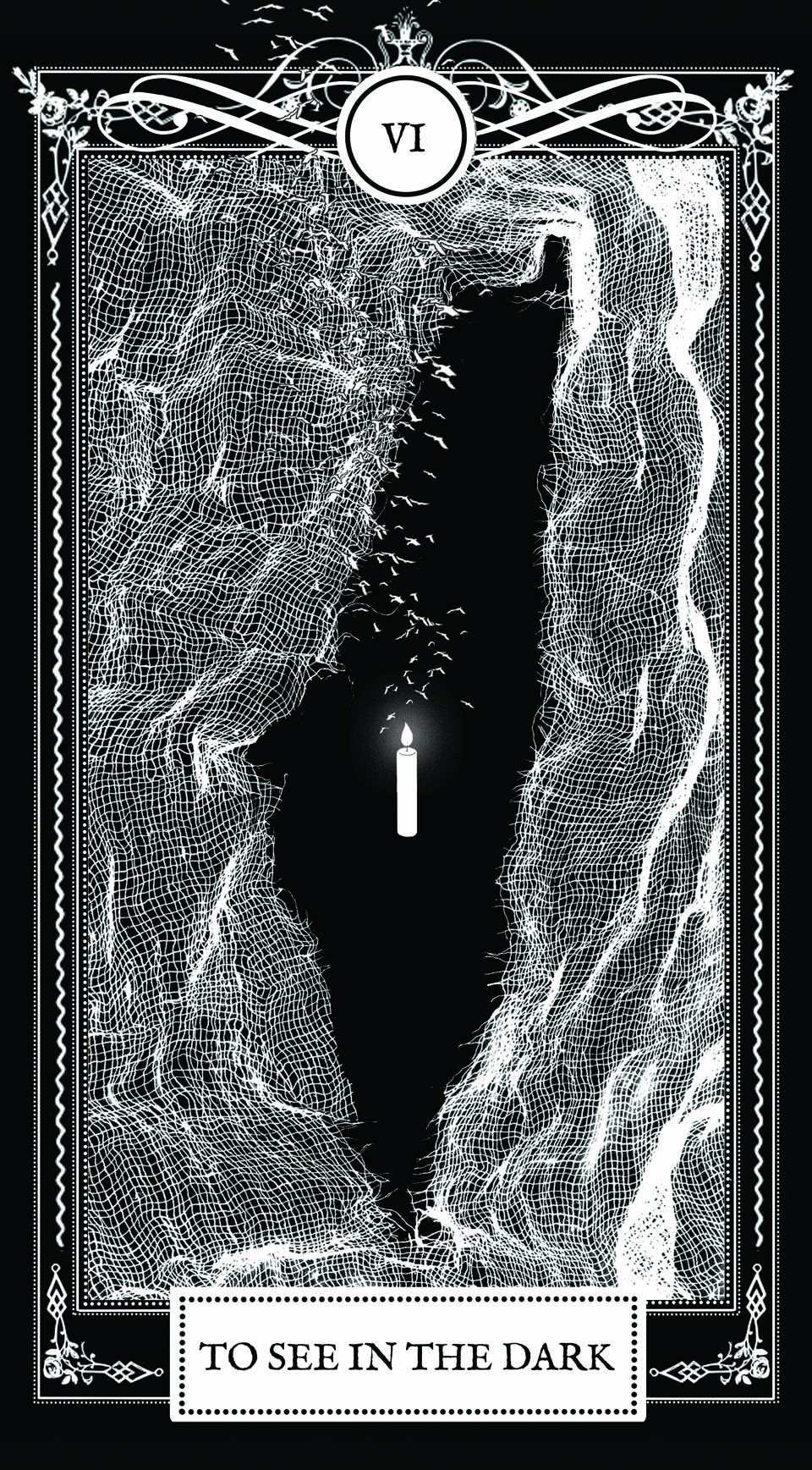

The book that emerges, To See in the Dark, is a different kind of writing. It’s not academic writing at all because it can’t be both sides. It can’t be judicious and balanced. And one of the things that pushed the writing as I began to do it was to think, “I’m coming very much from a point of view of the crisis of what you might call ‘the Jewish subject,’ ‘the anti-Zionist Jewish subject.’” But increasingly I realized that mattered much less than what it meant to be Palestinian and how my work might be legible to a Palestinian audience. And this became very clear in the book project, thinking through my use of language. So yes, obviously genocide, but also not using the passive, as the mainstream media do: “20 people were killed.” No, “the IDF killed 20 people.”

To not euphemize. And to not minimize. To not pretend that this is not what it is. Even the call for ceasefire, yes, of course you want the war to stop, but that’s simply one part of what’s going to have to happen.

On March 28, 2024, feminist activist and thinker Silvia Federici told a packed house in New York City:

“Palestine is the world.” She had said this before, yet her words landed differently in the wake of Hamas’ attack in Israel on October 7, 2023, and the subsequent onslaught by the Israel Defense Forces

(IDF) on Gaza. As Federici’s words reverberated intensely around the great hall at Performance Space on First Avenue, they were repeated by every other speaker there. I still see the effect that these words

have on people when I’ve quoted them. There are two key inflections in the phrase “Palestine is the world”: to think Palestine globally; and to see it in an anti-racist, decolonial, and feminist framework. To

see Palestine from the “outside” is not to speak for Palestinians but to associate with them in the global solidarity movement that has become a form of intifada (uprising) in its own right. –Nick Mirzoeff, Introduction, To See in the Dark

One of the things that I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about is rubble, because that’s what Gaza has become. A minimum estimate for clearing the rubble is 15 years. So the active phase of this genocide is at least 15 years. For me, it was a series of steps to realize the boundaries of what I had to deal with got further and further away. This means you’re looking backward. You’re looking to causes. You’re looking to histories. You’re looking to a very much changed present. And you’re looking to a very difficult to imagine set of futures. And that’s what writing does because it’s always multi tense, right?

That’s when I started realizing a collapse of the possibility of something called “an anti-Zionist Jewish subject,” entailing a willingness or necessity to leave this position so as to get to places faster and quicker. I can’t know what it’s like inside Palestine. I can’t even begin to imagine. But there’s an outside dialogue that needs to happen, a requirement to bear witness, and a requirement to acknowledge the martyrs who have been created. 45,000 people, at least right now, most of whom are women and children.

Alex: I am very taken by this progression that you expressed about audience, starting between and amongst Jews—progressive, anti-Zionist, non-Zionist, and more. I’ve been in deep conversation with you and others in that space. But you express a changed understanding of your audience as Palestinians. And then you made a comment, “the position of anti-Zionist Jew is no longer tenable.” Are you not speaking from this position? Have you shifted?

Nick: I think it’s not a position, in that I am taking up the old fashioned work of deconstruction. It’s an impossible position because the “Jewish” part of that is so colonized by Zionism, by the occupation, by the basic laws of the state of Israel. One will have needed to have accomplished anti-Zionism in order for it to become possible to be Jewish in the way that you and I, and I think many others, want to be, which is not particularly involved with “Judaism” as a matter of belief and daily practice and observance but rather as a question of descent and dissent.

I think now we have to acknowledge the work that needs to be done to get to the place where it’s possible to be what we have wanted to be, which is a person who can say, “yes, I’m a Jew,” that doesn’t immediately start to claim citizenship in the colonial nation. In the same way that you’re talking about this situation as “the interval,” I think we’re in a place where one cannot say that this phrase currently is stable. We need to put all the emphasis on the front half in order for the second half to begin to become possible in a way that we probably can’t yet quite know what it will mean.

Alex: All the emphasis on which front half?

Nick: “Anti Zionism.” In order for it to become possible, to be a different kind of Jewish person, a whole set of processes of abolition would have to happen. And that is so hard to even imagine now in the midst of it. So, one can only think of it in steps, as process. I think this is something we can learn from the Black radical tradition: abolitionism has always had two horizons. One is the moment where the entire prison industrial complex has been closed, and then the other is practicalities of the day-to-day.

Here, I’m saying genocide, “come for me if you want.” And I may lose that contest. As we’ve seen previously with McCarthyism, eventually what happens is there’s a point at which there is enough courage of enough people who stand up and just say, no, to be too hard to see us all. And because I’m a tenured full professor and I’m relatively late in life, I think it’s incumbent on me to be one of the first, rather than saying, as we have seen so often in our social movements, that the young people, the precarious, the adjuncts, are the person that takes the risks. We’ve got to step up.

Alex: So you are suggesting that these words should be “published” on my blog, just as you are publishing your book, as an act of solidarity, defiance, and producing, in action, through writing and speaking, the kind of Jews we hope we might one day be.

Nick: It’s a rehearsing, when I speak to you. Because I trust you. And this is part of a set of conversations that have happened over time. We’re practicing as it were, what it is that I think this new solidarity means.

And it’s the same with that writing practice where I’m writing to someone like you, often directly. That’s how I find out what I think. It’s not that I think it, and I write it down. It’s through the practice—whether it’s the practice of this kind of conversation on the blog or through the practice of writing—that I figure out what my position has become and it doesn’t stay the same.

And that’s why it’s important to use electronic media and other forms of almost instant dissemination. Only then can we keep pace with what’s a very dynamic and changing situation. And the best thing that could happen will be that this writing comes to seem markedly irrelevant.

- Here is a summary, “4 questions and 21 audiences at the new year,” of the writing I did from November 20 to January 1, 2025 via the first rubric for my self-imposed practice, one where I blogged, seriously, about every audience I put myself into. ↩︎

- This is my sixth such interview since 2025 began. The first was with my boyfriend (about the intimate audience, writing, and depression in the interval); the second with Michael Mandiberg (about being audience to another’s need, as that person is careproviding for a partner undergoing chemo); the third with Aymar Jean Christian (about his work on the African-American cookout as a model for community and mediamaking); the fourth with Dan Fishback (about his show, “Dan Fishback is Alive and Unwell and Living in his Apartment,” and what this raises about alienation and solidarity practices with the chronically ill and those in Palestine); and the fifth with Chloë Bass (about our collaborating via teaching a feminist class on archives after the inauguration). ↩︎

Comments

5 responses to “rehearsing solidarity by writing and speaking”

Thank you both for this exchange. I very much look forward to your book, Nicholas. I have been entertaining much the same set of questions about the possibility of being Jewish since the Israeli attack on Gaza in 2014. I thought of it as my “legitimation crisis,” until I understood it as a dilemma that I wanted to transform into material action. I find yours and Alex’s conversation inspiring.

Have you done any of this transformation, Nina? What forms might it take? And thank you for responding.

[…] Crazy! In this short-term repurpose of the blog, twice now, people I’ve been talking with (Nick Mirzoeff on writing his new book, C. Jones on writing poems) discuss the power of writing for an audience of […]

[…] social media, reminds me that communities of practice are real, even as we are dispersed; that we continue to learn with each other; that documentary does many kinds of ethical and political work across different and competing […]

[…] It’s a rehearsing, when I speak to you. Because I trust you. And this is part of a set of conversations that have happened over time. We’re practicing as it were, what it is that I think this new solidarity means. – Nick Mirzoeff, rehearsing solidarity by writing and speaking […]