I love a matinee: a movie theater spattered by cineastes, the retired, and other seekers. When I joined said audience everyday for a month in June/July 1999 at the Regency Academy, a discount art house in Pasadena (pregnant, hot from walking a mile there, looking for a way to get through the last month), it was mostly populated by people in need of the cool and often shelter, too. No matter the inspiration, a matinee transforms a tepid afternoon into a warm sponge for color, darkness, sound, and other people. Film viewing becomes more languorous and decadent (even if discounted). You and your fellow viewers join together to fill the yawning space of the midday with something more rich (whatever the movie).

Yesterday, my boyfriend and I, like many indulging in this favored day-after-Christmas activity, joined the audience at our local cinema, the BAM Rose. We were there to see the matinee of The Nickel Boys for reasons similar to those listed above, albeit in a different climate as well as chapter in my life and the country’s.

The film is as interesting and stunning as critics have opined. Admittedly, I have read nearly everything by Colson Whitehead, and Nickel Boys is nothing like my favorite. A good read, sure, but saddled by a tricksy frame that, even once I re-evaluated what knowing it revealed, didn’t seem to make the novel, or me, much wiser. The film version takes up this narrative trick (no spoiler alerts) as a formal invitation to explore, indulge, and almost blow apart traditional cinematic point of view. Now a treatise on Black male visual perspective (which is only true for the book retroactively), we (learn to) see from four standpoints across the film’s two-plus hours. Hollywood’s to-be-expected omniscient gaze, only provided for interactions between the two male leads—and the only look in this film that feels anything like normative or even comfortable—takes up a scant few minutes of screen time (and could still be surmised as the POV of one of these two characters, depending on your ultimate read of the film’s narrator).

Even without the film’s overt tutelage in ways of seeing, the surrounding writing allows us to understand all this visual and narrative invention as an exegesis in what RaMell Ross calls “sentient perspective.” His first film, a more remarkable, spare, and experimental essay on Black lived experience and its sight, Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018), has similar goals, although gained through different inventive documentary cinematic means. Actress Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor understands Ross’s work as a response to “the absence of intimate, complex storytelling about Black life.” Actor Brandon Wilson continues:

For audience members who are watching all of this happen from the perspective of these two, they can’t separate themselves the way they can with other films. They cannot be an observer. You are brought into it, and because of that, I think there is a very special experience you feel while watching it where you are connected to, for lack of a better word, the humanness of both Elwood and Turner. You want them to live as long as possible.

Ross’s deeply moving and also political project—building and sharing Black perspectives through experimental narrative cinematic forms that might open an audience to empathy via an observational and embodied visual path to shared humanness—is now playing on screens across America. This is happening during what I have been calling here, the interval (by way of a different [queer and trans] Black cinema experience, and the thoughts of other Black intellectuals and filmmakers of color). Yes, learning from Ross’s thinking and practice is highly relevant for this project—a commitment I made on this resuscitated blog to write a careful post after and about every time I enter an audience between election and inauguration so as to better equip myself in strategies of coming together by discerning the many features of communal engagement.

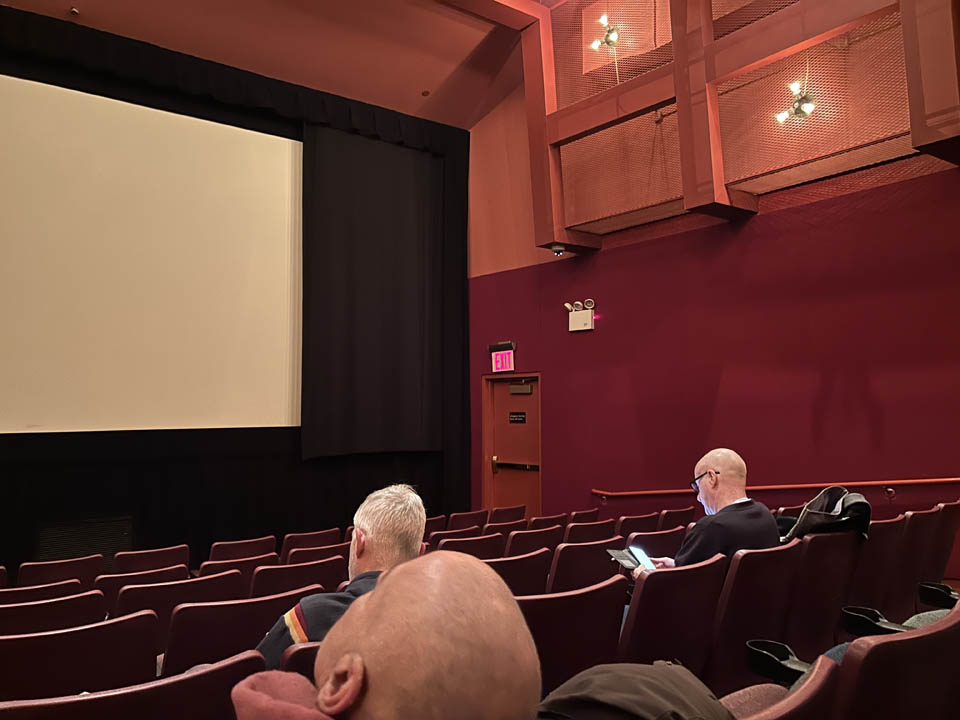

But what seems most notable to me, writing as I must in my practice from lived encounters of audiences, is that our rather paltry one—at least as seen from my frontal point of view below—was entirely populated by balding white men (a feature shared with the man with whom I attended, not pictured).

In Black Skin, White Masks (1952) Frantz Fanon anticipates and fuels what will be some part of Ross’s contemporary cinema project: “Superiority? Inferiority? Why not simply try to touch the other, feel the other, discover each other?”

Yes, part of being in an audience is knowing and feeling the other, perhaps particularly because in most movie screenings interaction is not required or common. The transformation Wilson anticipates is internal even as it is communal. And, given that I saw the film in Brooklyn, there actually were as many Blacks as whites in our small audience—mostly fathers and their teenage daughters (they all ended up sitting behind me so are also unpictured).

White male bald heads framed the screen for me (a critical counterpoint to the back of the head of a Black, dreadlocked male that provides one of the film’s four perspectives). And what this raises for my project is also critical: putting into stark attention the role of framing and identification, narrative cinema and its in-person audiences. Just as was true about the WASPs and Jews at the Hanukkah Celebration I attended and wrote about previously, these audiences are gathering in America in late 2024. I have no idea where people stand in this divided country, why these white balding men came out to this matinee on the day after Christmas, what they know about Black experience or cinema, or thought about after. I can not learn their beliefs, although we might hope them to be affected by Ross’s.

Fanon writes: “Sometimes people hold a core belief that is very strong. When they are presented with evidence that works against that belief, the new evidence cannot be accepted. It would create a feeling that is extremely uncomfortable, called cognitive dissonance. And because it is so important to protect the core belief, they will rationalize, ignore and even deny anything that doesn’t fit in with the core belief.”

So, here’s where food enters the picture, again. While most cinema theaters are not places for a back and forth (unless there’s a Q and A, and this is still not particularly participatory; or the audience is schooled in interactive attendance, by way of the Black church, as one example), many of us continue to think and talk after we see films, extending the reach and power of the audience into dinner conversations or drinks or walks with friends, the writing of criticism or blogs posts, through further reading, and across other formats where core beliefs can continue to be expressed and challenged with a powerful text, like Nickel Boys, as evidence and excuse.

I spent dinner after the show with one bald white man. Gavin, a writer himself, had also read the book. We spent an intense hour over pizza and beer trying to make sense of artistic perspective in racist America and this film about it. More a relay than a singular event, taking up a space in the audience of anti-racist cinema, and continuing this elsewhere, can be part of a process of discovering the other.

Comments

2 responses to “white heads, Black film”

[…] Just yesterday, when I knew I was going to go to a second indie feature at a NYC art house in as many days (Almadovar’s, The Room Next Door, not playing in Brooklyn, sigh, […]

[…] family dramedy (so like and unlike my own intellectual Jewish clan in Boulder, CO; my third matinee audience of the season, albeit not at an art cinema house). I was greeted with a different sort of […]