The meta is my downfall and my delight, I suppose by definition. Work that refers to, returns to, revisits itself—its forms, its theories, its pleasures—pleases me. This temporary blog reprise, a practice I have now defined to occur over the interval between election and inauguration, began on November 20, 2024, when I returned to Christian Marclay’s The Clock. Looking back, I began to (re)consider cinema and blogging as dated and companion technologies of time capture. Through a return, I could also see these as dense labor practices (in the making, in the watching, in the reading) that have become harder to perform in their digital adaptations and on the corporate platforms that run them.

This current practice pleases me, by definition I suppose, by creating patterns of behavior that follow principles of being and doing in community. Its purpose is its doing: a more dedicated attention to participation than social media allows. If (its) reading is produced, another format of a labor of love, that is a delightful residue. And of course there will be the lasting. I can return to this, and might, and do (all the links are to previous posts save the six at the top, which gallop across previous projects in recursivity, over time and format, from Learning from YouTube to The Watermelon Woman).

Our current interval is hard, and sad, and scary. My going somewhere and then having to blog about it provides not comfort, nor a positive outlook, as much as a model to get by, stay grounded, learn with others, name where we are, and ways we might go forward together. My process has led me, with some alacrity, to the question, affordances, and nature of the audience: online, off, hybrid. sure; academic, art, community. yes; interactive, pedantic, authentic. indeed; but also virtual, commodified, habitual, cruel, uncertain, and false. It now leads me here: is the (feminist reading) group an audience?

Taking quick stock of where this brief but growing practice has taken me, I learn at least 4 things:

- an audience: [is] a time and place of reception, quiet, participation, and connection outside of (same-time quicktime) over-mediation.

2. To be in an audience [of experimental Black trans cinema] can be a practice in shared space and time predicated on being open and generous, supportive and interactive, activated and awed by the intense and sustained work of others, as well as those witnessing in the room with you.

3. An audience can be a community when:

- power, knowledge, and vulnerability are distributed

- connections and differences between individuals are acknowledged and respected

- a named political, social, cultural, or institutional goal hails and connects

- work is made and shown and discussed with an articulated objective

- there are opportunities to speak and to listen

- food or drink is enjoyed

- there is time and opportunity to be social

- history enters the screen

- next steps are possible

or, it is small enough to stay known; built through and about history but alive in this present; dependent on political or artistic commitment; dialogic; and as Susan [Mogul] said about her long career, “outside the mainstream.”

4. Social media is not the audience as community that I have been trying to better understand here.

Easy. My reading group is an “audience as community,” in light of items 1-3. Hard? Delightful? My reading group last night became meta as pertains to item 4. Look how it dangles, self-reflexively, a sad-reverse in negative of itself, and all above. But, given that I share it (and all) here online, and then on Facebook, Instagram, and bluesky, daily, watching the audience grow or shrivel, I must see the social media (not) in me.

My reading group has been meeting for several years now. Initially organized by my friend and fellow punctum books author, the writer Leora Fridman, to read the oeuvre of Annie Ernaux over time and in a community of feminists with keen commitments to writing, reading, fact, and fiction (and poetry), the group has followed a peripatetic and reckless path post-Ernaux, from Hannah Arendt to Janet Malcolm, and many more, landing last night at Naomi Klein’s “trip into a mirror world,” Doppleganger.

We liked the book well enough. But what this group of 8—all younger than me, cis-gender female, impressively professional, and therefore hyper-focused on Klein’s “brand” work in relation to Wolfe—connected through, deepened into, laughed and worried about, was “if there was a way to be on the internet that doesn’t spiritually deform us?”

I listened.

Their (my) (Klein’s) relationship to the internet and social media more specifically, is meta. They can’t do it without knowing it without wanting it and hating it and needing it and leaving it and turning it back on for memes (of Luigi) and locking it in a box which you pay $99.99 a year for and turning to it for comfort and laughs while knowing it uses us and still needing it for buying stuff and jobs and audience and …. not community. This meta/Meta© approach distinguishes them from those who aren’t there (yet): people they love; those who don’t get it; users who are not of this community.

If social media is the doppleganger of community, the meta the up- and in-side of myopia, and the fascist not out there but inside us all (with thanks to group member, Dena Beard), then the upside-down reality that Klein proposes, and I have insisted upon since the previous inauguration—where tweets are weapons, and guns are memes, and none (and all) of these are (not) metaphors—then what I am trying to understand is:

how is or could be social media the audience as community for the interval?

My writing here has always been quasi-professional and meta, as an embedded scholar/practitioner of critical internet studies. So over the last three weeks, among many things, I’ve been attempting to distill, for myself, the affordances of the pandemic technologies at our disposal given their fundamental role in where we are now and what we will become; how we will live and how we might not be deformed.

As one audience member in my feminist reading group—listening, drinking, watching, contributing, struggling—I learn how they (we) perceive and experience our relations to the digital by way of demographics, habituated practices, mercurial memes, and our “personal” platforms (boomers do x, vigilantes do y, children do z … to their imminent destruction). But if that/this place is our bottom up reality, and our dark side a possible light, then these false but foundational projections of digital connection and community are a key part of the problem (and the pleasure).

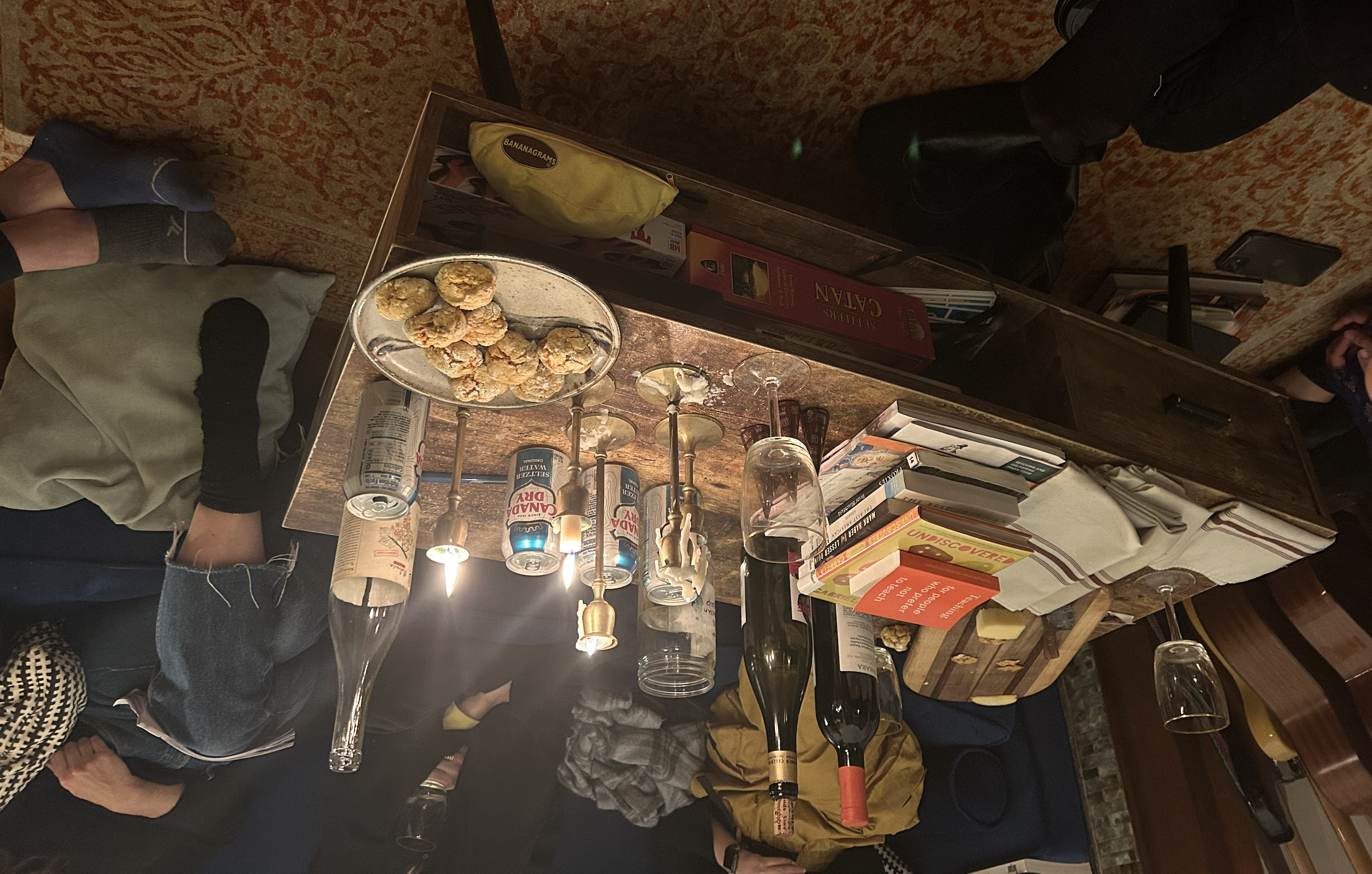

When is the meta not a downfall? How can we be delighted by our evil twin (within?) If I start by looking at my worst self (not the ideal communities that feed me), what do I see? A sky of carpet, the comforts of candles and cookies, a world with no gravity.

Comments

4 responses to “meta: one feminist reading group”

[…] evening’s culminating circle was the only part of the Chanukkah party that felt like “an audience.” Damn … I would need to write (see Afterward below). And it was me who had made it so, […]

[…] as intelligent passionate devotion). I had learned about the book because Gwen is a member of my feminist reading group (an audience whose affordances I have also interrogated […]

[…] through a set of processes to guide our attention and connection. Why we so often need a piece of art or a sermon, some food or a shared problem, a person or a lecture, to make that vital […]

[…] read it. It’s quite eerie to me because I’ve been thinking about how to credence the unknown and imagined “audiences” of the internet. Here I am, back on my previously dead old blog, and […]