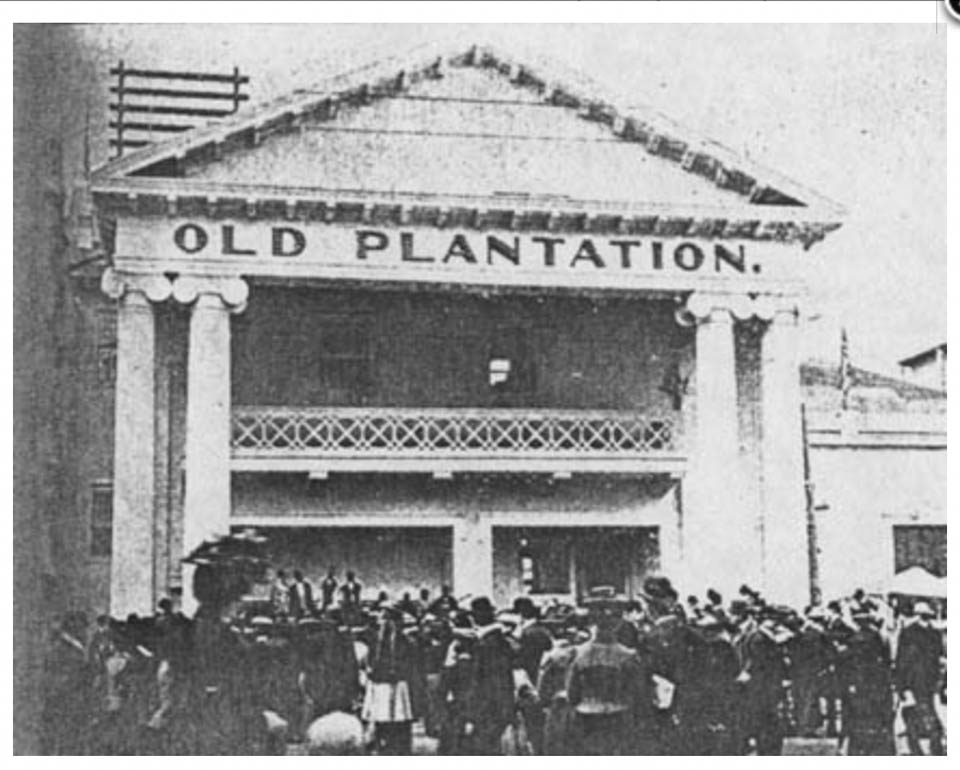

I had the distinct pleasure of attending the Columbia Sites of Cinema Seminar on Thursday night to hear a lecture by Dr. Allyson Nadia Field and a response from the equally impressive Dr. Raquel Gates. Professor Field shared her current research on some of the extant early films that recorded business on the Old Plantation, one of several bigoted and anti-Black concessions lining the Midway of the Buffalo Pan-American Exposition of 1901. Field’s important contribution to an historiography of international fair-goers paying to see other humans performing racist depictions of themselves as entertainment contributes to her research group’s project of unearthing and decoding the visual afterlife of slavery.

Field argues that these film records of African-Americans, paid to perform fancifully benign depictions of the labor and leisure of the enslaved (some of these workers had been enslaved, most notably “Laughing Ben” Ellington whose images from this fair have entered American culture more broadly; most of the other performers were the children and grandchildren of former slaves), while living and working in life-sized cabins and fields, and on working spinning wheels, all the while under the shadow of the attraction’s huge and cruel but ostensibly stately calling-card, the aforementioned Old Plantation, and across from another attraction, In Darkest Africa, produces an ongoing visual life (not afterlife) of slavery.

Building on the interests of this, my reanimated blog (this is the third effort in as many days)—what we might learn from our mediated technologies’ various relations to time given the brutal and frightening one we have been sliding into—I was most taken by Field’s proposal that these films lock African-Americans into a past and/as perpetual present, a “flattened temporarily,” by way of cinema. The films record a racist performance 35 years after slavery’s end, which would have been known to the audience at the Exposition (at least the past part). But the performance’s movement qua film negates that this was indeed an afterlife of a (fake) past plantation and its people. Instead, Field argues, the camera lens and then the films’ distribution, serve to evidence a merry life at an extant but old plantation, cementing slavery’s ongoing existence in later presents.

What does Field’s work help me understand about time, cinema, and this our dark present in light of technologies of history, memory, and knowledge? Well, certainly that moving images need context for their reception, what I have previously called “holding environments,” and that, as Sam Feder expressed in another project: “cultural myths often lead to dominant ideologies.” But here, I cite my own and other’s previous work about our new king’s old hold on “fake news” (which really is so passé; how can that be?!). So what is new here, for our specific slide into darkness? Perhaps this very old practice:

Get thee to … an historian!

In this, an awful murky window between the racist what-already-is and what will become an even darker reality, a what-will-be organized by new leaders with their own violent, punitive, and fascist take on some Americans and much of American history, I am, frankly, and like many others I think, finding it hard to read the internet’s requisite real-time hot-take, post-game wrap-ups. The internet has been built to feed us in just this way: an unspooling fast replaceable mad-cap screwball of chatter. All those writers are doing their job just as we do ours: write, read, share, quote, confuse, conjecture, preach. Our un- or low-paid work within corporate-owned circuits of knowledge are a good part of what got us to the mad King, twice (I speak of this endlessly, elsewhere, and with many others, so am moving on here, but can name lack of belief and amplification of violence as two of internet-fueled root causes).

But, there are other traditions. I suggest that one way to live within today’s darkness—to understand it, contextualize it—is to listen to and learn from workers with deep, slow, and small knowledge sets, built over careers dedicated to understanding with detail the darkness (and light, or perhaps resistence) before us.

While it might sound like I am suggesting getting closer to facts, evidence, and objective reality, this is not what I believe Historians do exactly, not entirely what I want from other humans, nor what helped me so much in my hour in the spell of Dr. Field’s lecture and PowerPoint.

History, like all forms of human knowledge production and circulation, has established methods of research, writing, and explication. It is partial and subjective, and also strives for rigor and evidence.

So, I say get thee to an historian! not for truth but because being in their presence, as they perform their very difficult labor (as if it was natural or easy) of transmitting untold hours of research about some far-flung residual of previous human experience into digestible depictions, is an antidote to both AI doing that badly and/or the quick turnaround of today’s chattering opining classes doing it too quickly and often for reasons that perpetuate or grow the very darkness under review.

How the historian embodies, owns, authors, and performs her knowledge moves and holds the past in the present and through one body and her carefully made slides while opening time and space to include an audience.

In this respect, when I say “get thee to … a historian,” I make two related suggestions, as remedies, today at least, for what ails me. One: travel there. And two: turn off other streams in her presence. Get thee to a knowledgeable person in a different place from your home/office/work/family/computer/screen. If you are not leaving the house for reasons of caution, illness, or the care of self or others, try to practice creative strategies of transition and diminution. When you arrive to the historian in her zoom room or previously recorded lecture, you too can enter with a head at least partially cleared of the other browsers, windows, chatter, and screens that overwhelm us all (no need to romanticize what actually happens in rooms of co-presence).

And thus, get thee not to … a nunnery (although this might be another great choice for some quiet meditation around other queer women) but to … an audience: a time and place of reception, quiet, participation, and connection outside of (same-time quicktime) over-mediation.